Phantom Regiment: Battle of Normandy

by Asher Pirt

To the grey fields of Normandy,

Came Phantom in their hordes,

Wielding their ruddy chinagraphs,

Much mightier than swords....

Introduction

P badge to indicate Phantom Personnel.

The aim of this article is outline how GHQ Liaison Regiment (Phantom) was organised, employed and what it managed to achieve in its relationship with the Canadians during the Normandy campaign 1944-1945. It was an essential element of command and control in Normandy. One military historian has described the Liaison Regiment as an element of a “directed telescope” for the Commander-in-Chief. The experience of the First World War for both the Canadians and British must have influenced the argument to have such an organisation or Liaison Regiment. Phantom had its origins in the No.3 Air Mission formed in 1939, which was commanded by Wing Commander J M Fairweather DFC. This Mission was concerned with the locations of friendly forces in the event of combat operations. It was expanded with permission of the Air Marshal Sir Arthur Barratt and War Office to include a military portion. Lieutenant Colonel George F Hopkinson MC who commanded the military portion and following the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force managed to gain War Office permission to retain and reform the Mission as No.1 GHQ Reconnaissance Unit. The designation was changed to GHQ Liaison Regiment in January 1941 to avoid confusion with the newly formed Reconnaissance Corps.

Phantom’s role was to provide early information on the progress of the battle, and on other matters of immediate importance, primarily for the higher command holding reserves capable of influencing military operations also for other commands directly concerned in the conduct of the ongoing operations. Phantom had no duties in the field other than the collection, passage and dissemination of information. In the battle information was obtained by liaison, intercept (J) or personal reconnaissance. Phantom was a Second World War liaison and information organisation with its own secure communications. The commanding officer in the Normandy campaign was Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Henry ‘Sandy’ McIntosh. Widely regarded as ‘charismatic, a gifted orator, with a lively sense of humour and a decisive personality’. Born in 1902, in Kirkcaldy, he was educated at Merchiston Castle School. He joined the family business and was commissioned into the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry. Joined Phantom in 1943.

High Command and Phantom

Phantom was involved in campaigns and operations in the middle east, the fall of Greece, the Dieppe raid, North Africa, Sicily and Italy prior to the invasion of North West Europe on 6 June 1944. Air Marshal Barratt praised the Phantom for its contribution to the awareness of the situation in France 1940. He sent the following message:

"Heartiest congratulations on most useful information with which you have kept us supplied. It has been invaluable. Please inform all concerned"

Staff Officer at BAFF wrote on 28 May that when Phantom, No.3 Mission closed down the ‘main source of information in the North’ was gone! The fall of Greece led to the capture of most of the Phantom detachment commanded by Miles Reid sent to report on the battle. However their conduct led to Sir Jumbo Wilson becoming one of its biggest fans. A report on the work of Maj. Reid’s Squadron in Greece by a Senior Officer on the Staff of C-in-C explained:

Two signalers at work

"The GHQ Liaison Squadron in Greece was quite excellent. It more than justified itself and I do not know what we should have done without it. Never once did the Squadron fail in its duty by day or by night. The Squadron was well trained, keen and well commanded"

Operation CRUSADER indicated the utility of Phantom patrols in the western desert.

The Dieppe raid was a debacle in many ways but a study of Phantom communications by Secret Intelligence Service Wireless Chief Brigadier Gambier-Parry proved that Phantom had once again impressed Higher Command. Captain Alastair Sedgwick’s patrol had reported extremely well on the tactical situation with No.4 Commando. However, the loss of a Phantom patrol commanded by Michael Hillerns was very sad. The patrol attached to the 2 Canadian Division was never to come ashore and, in the end, returned to a destroyer and returned to the UK. While the experience of Phantom on exercises with Home Forces including First Canadian Army appears on the whole positive, Phantom had been perceived to be negative with Eighth Army. It was found that ‘Y’ Service was able to intercept German intercepts decoded Phantom communications before the Phantom messages reached their intended destination. By 1944, the messages within the Phantom net were very secure using a Phantom codebook and one time pads.

Montgomery appears to have been still unimpressed by the Phantom Squadrons on active service in the Tunisian campaign and Italy. When he and staff met the ‘E’ Squadron Leader over lunch, ‘he stressed his chief objections to Phantom in the past, viz: the personal reports of junior officers, the reporting of intentions and the foreign and almost Papal control of RHQ from Richmond’. The result of the meeting was the break-up of this Squadron. Though it is clear by 1944, Phantom had won more adherents to the Phantom way. Montgomery as overall Commander of 21 Army Group remained concerned about its activities. He had to be won over by the need for a liaison and information organisation with its own communications. One promise was that messages would not be passed beyond Montgomery. The inclusion of ‘J’ into Phantom was as a result of Montgomery’s use in his campaigns.

First Canadian Army Phantom

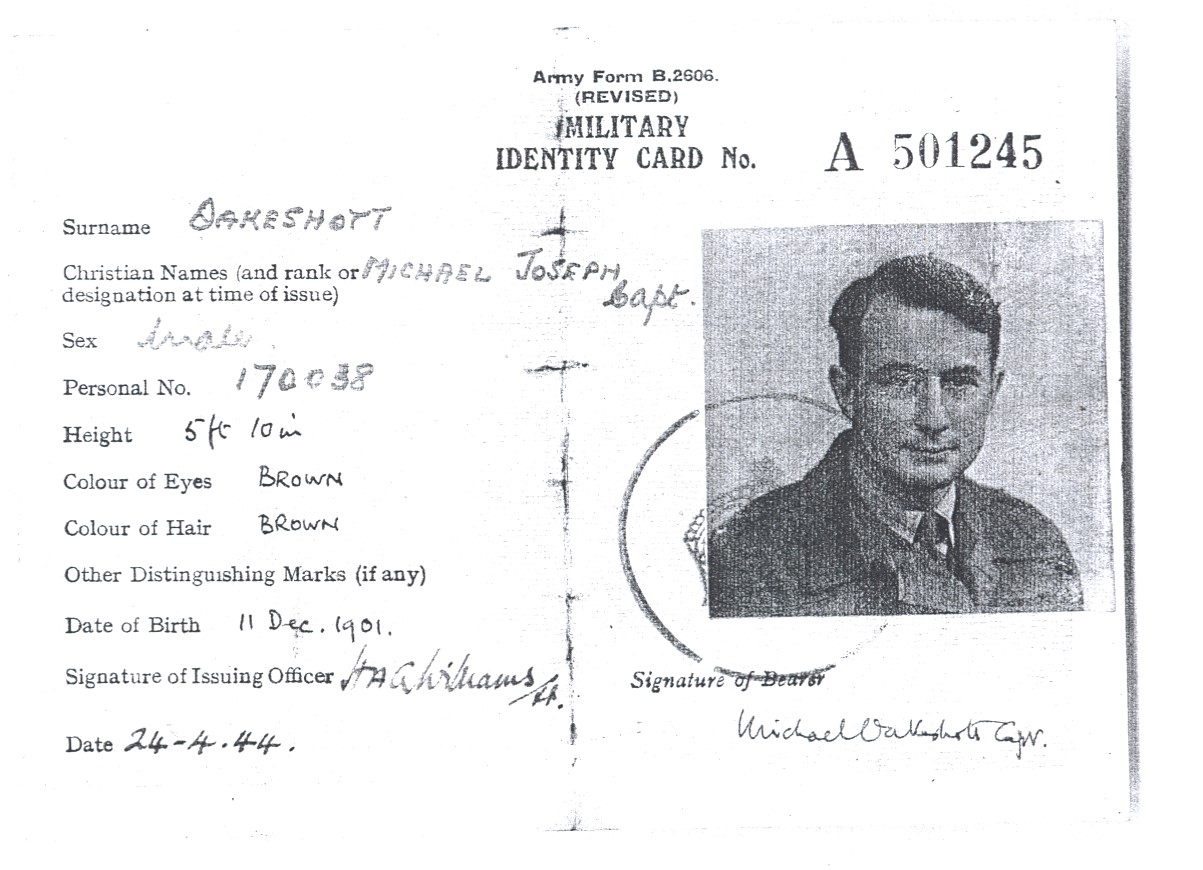

Michael Oakeshott (ID) the great philosopher and admin officer

The First Canadian Army Squadron was commanded by Major Peter D Pattrick who had joined Phantom in September 1940 and had served in the ranks of the Territorial Army before the war. Commissioned into the Royal Artillery in 1939. The philosopher Michael Oakeshott was the Administration Officer for the Squadron. A Squadron for an Army of two Corps consisted of (a) the Squadron HQ comprising operations and intelligence troop, Signals troop and administration troop (b) Two Corps patrols (c) Six Phantom patrols (d) Two ‘J’ troops. For an Army of more than two corps an increment of one corps patrol and three Phantom patrols was added for each additional Corps. ‘B’ Squadron patrols were named after Birds: Kite, Harrier, Fulmar, Tern, Kestrel, Eagle, Gannet and Merlin. Later, on 6 August 1944, the ‘J’ Troops would also adopt Bird names: Skua and Cormorant. ‘B’ Squadron HQ was always located at First Canadian Army HQ. A detachment of two officers and six other ranks usually worked inside the Army Operations Room. The deployment of the Squadron was arranged by Maj. Pattrick directed by the Chief of Staff or GSO 1 (Operations). The Corps patrols were permanently allotted to Corps HQ. Officer patrols were allotted according to the situation to formations and units. Patrols both those in reserve at Squadron HQ and those deployed with formations may have been sent on special missions, to provide information required not only by G staff but also by Royal Engineer, Q and other branches. Patrols were frequently deployed so as to obtain flanking information from other Phantom patrols.

Information received at Squadron HQ was checked and passed: (a) In clear, by direct land-line, to the detachment in the Army Operations Room. There copies were made for distribution of messages containing intentions for more than 36 hours ahead is restricted to GSOs1 (b) In high grade cipher by W/T to Regiment HQ. It was the responsibility of the Phantom Officer in the Army Operations Room to (a) Keep a full record of Phantom messages and be prepared to answer questions and to explain the situation as shown by Phantom information (b) to add explanations on ‘J’ messages of “jargon” used, indicating where possible actual units in such phrases as “the friends on my right”; and to draw the attention of the staff to cases where ‘J’ messages are confirmed by other sources and to any general trends revealed by ‘J’ messages. (c) To note on any message the reference of previous messages on the same subject. (d) to keep the staff informed of which intermediate HQs are receiving Phantom information and where such information originated. (e) to pass any necessary documents and information from Army HQ to Squadron HQ. Squadron HQ sent out by Despatch Rider to all patrols a written situation report summarising the position on the whole Army front, at least once every twenty-four hours. This was made available to the formation with which the patrols are deployed.

Two Canadian digging slit trench with Phantom patrol jeep behind

An officer patrol was normally allotted to a Division. In cases where the patrol was also providing ‘J’ information, it might consist of two officers and with armoured divisions be provided with an additional W/T set in a Jeep to enable one of the officers to go forward to Brigade HQ. Information was obtained: First, from the Senior Officers of the HQ to which the patrol is allotted and passed back to HQ in high grade cipher using the Phantom codebook and one time pad. Second, from listening to the wireless nets of the Division. This information was sifted and if of value passed back to Squadron HQ in exactly the same in which it was received, at the same time it was pushed to the Division HQ. It was the responsibility of the patrol officer to decide what nets will be listened to. Experience had shown that it was not normally necessary to listen below Brigade command nets and three sets were enough to cover a Division front. Each patrol had two Dispatch Riders available to carry copies of orders, traces, code words etc to Squadron HQ via the Corps patrols. Intentions were normally sent back by Despatch Rider. Patrol officers particularly when sent on special tasks were often required to send written reports or to report at Army HQ in person. Patrol officers included Earl of Rosslyn, Alan Laurie, Peter Ling and Brunel-Cohen. Laurie had served in North Africa and Sicily with Phantom. Brain had been employed as a patrol officers in the secretive Auxiliary Units. These patrol officers did not report their own opinion or conclusions except when directly ordered to make a personal recce, under the instructions of Army HQ and with the approval of the commander concerned. Otherwise all information was obtained from responsible Senior Officers; the source of such information is always included in the message to Squadron HQ. Alan Laurie reported on the morale of troops from his personal opinion on the insistence of High Command when friendly forces were bombed by the Royal Air Force early in the battle. The method of obtaining ‘J’ information was known to all Senior Officers receiving it, and it was treated by them as unconfirmed.

The Corps patrol had two main functions: First, to provide information for the staff of Corps HQ by listening to the rear links of Phantom patrols within the Corps, or with flanking formations. The corps patrol had three receiver sets available for this purpose. The allocation of these sets was decided daily by G Operations at Corps HQ, and their decision was passed to Army HQ through Squadron HQ. Correction and answers to queries were obtained from Squadron HQ through the Corps patrol rear link. Secondly, acted as a clearing house for messages etc sent by Despatch Rider between patrols and Squadron HQ and provided patrols with information about future intentions and copies of codesigns, codes etc that were needed to operate the ‘J’ Service. . Each Corps (Kite and Harrier) patrol was provided with: (a) One 12 set mounted in a 15-cwt wireless truck, as rear link to Squadron HQ (b) Three R 107 receivers mounted in a 3 ton wireless lorry to listen to the Phantom nets within that Corps and within flanking corps. Each Phantom patrol was provided with: (a) one 22 set mounted in a white Scout car as rear link to Squadron HQ (b) One R107 receiver also mounted in the White Scout car to enable the patrol to listen into other wireless nets and thus obtain flank information. In the Normandy campaign the patrols utilised the No.22 Set which had a booster set invented by Peter Astbury that allegedly made it as powerful as the 12 Set. This tended to upset other signallers nearby and its use during battle could be blamed for the failure of other signallers to get through.

A typical White scout car used in Normandy by Phantom patrols.

Flank information was provided at various levels by: (a) Grouping patrols concerning on one wireless net. (b) Using the available receivers of a patrol to listen to other patrol nets or to formation and unit command nets (c) Deploying patrols with flanking formation HQs. In this case the patrol officer already at the HQ and not direct from the staff of that HQ. When a patrol officer was sent to a formation of a flanking army he obtained the approval of a responsible Senior Officer of that formation for all messages he sent back. Similarly, when a patrol officer was ordered to report on a commander’s intentions he did so in a form agreed by that commander. On the other hand no formation other than Army through the Phantom Squadron commander gave orders to Phantom patrols –except Corps in the case of their own Corps patrols only.

It should be emphasized that the information obtained by Phantom was not limited to operational subjects. Great assistance has been given to administrative staff by providing admin information, particularly during fluid operations or when called on by Royal Engineers to provide information about bridges, bridge sites and bridging operations. Experience had shown that Phantom could provide and in fact had provided vital information to all branches, at all levels.

There is perhaps space here to add detail about MORSEX, which was a high grade cipher machine. The machine was invented by Phantom’s Capt. Astbury and its purpose was to send and receive messages in code. The machine was first tried out successfully on a major exercise ‘Blackcock’ which took place in October 1943 at Great Driffield. Initially, communications were established over ten miles. A message which by normal means took 14 minutes from originator to receiver but with MORSEX took only five minutes. The machine was manufactured at GPO factories at Dollis Hill. Its security was tested by Government Cipher Service. It was used initially in the early campaign in France but found that the machines needed more development to deal with conditions. On 4 August 1944, a decision was taken to postpone the use of MORSEX and machines were withdrawn. The War Diary pointed out that in the previous few days the Squadron had four patrols deployed all of them working on MORSEX but good results have been too intermittent to rely on MORSEX for operational traffic. The reasons for poor results appeared not to lie in the conception of the invention but in the workmanship of the machines. While machine remained in good order results were excellent. Both patrol officers and Other Ranks Signal and cipher operators liked the machine and would have been pleased to make use of it if its reliability could be improved. Capt. Astbury was with ‘B’ Squadron during the period when the MORSEX machine was in operational use.

The Battle for Normandy

Ian Balfour-Paul MC went ashore with 3 Canadian Infantry on D Day.

Peter Pattrick was briefed on 29 May 1944 as to where ‘B’ Squadron was going and given a hint of the actual date and, together with a token detachment, inspected and exhorted by General Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander. All ranks were now excited and interest maintained by orders to send two ‘J’ patrols to Portsmouth to help RHQ. However, spirits were apparently dampened the same evening by the news that only Ian Balfour-Paul would be in on D-Day. He had already been detached with his Merlin patrol to ‘A’ Squadron with Second Army in March. It turned out that ‘B’ Squadron’s orders were to send a skeleton Squadron Headquarters and four patrols with Canadian Army Advanced Headquarters about a week after D-Day and for the balance to follow at some unspecified date as the remainder of Canadian Army were fed in. Accordingly, Peter Pattrick detailed Dugan Webb’s (Harrier) Corps patrol to act in this capacity, controlling Rosslyn (Eagle patrol), Coward (Tern patrol), Brunsdon (Kestrel patrol) and Laurie (Gannet patrol). It was agreed that Peter Pattrick ought to go with this party and John Dulley was to bring the rest of the Squadron over later.

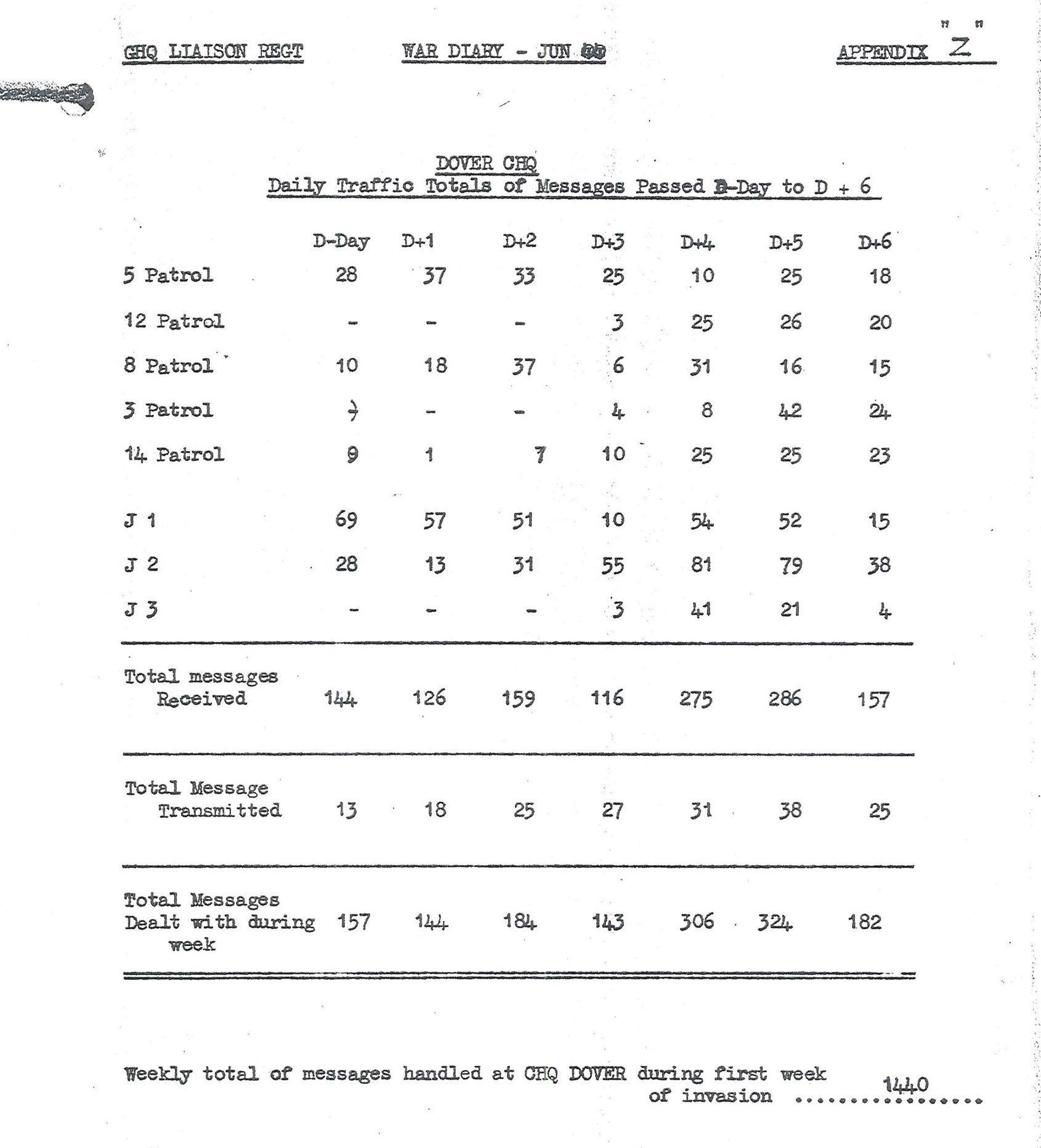

Merlin landed with 3 Canadian Division on 6 June. Its function was to liaise with the Canadian Division and keep 21 Army Group HQ aware of the progress of the Canadian assault. In addition, the patrol listened to the Canadian Division Contact Wave. The Merlin patrol layout consisted of one No.22 set with Astbury amplifier and two R.107 receivers. The 22 set and one receiver mounted in a White Scout car, one receiver in the jeep. Merlin was commanded by Ian Balfour-Paul who had been a school master before being commissioned into the Royal Engineers. His patrol consisted of an NCO and five other ranks. The patrol was delayed in landing but still Balfour-Paul managed to intercept communications and plot what was happening ashore. At once on the beaches at Arromanches, Peter Pattrick wrote that Merlin established communications with the UK “during a period of exceptional difficulty and enemy interference, continued to pass information of great as to the progress of operations”. Later, Balfour-Paul was awarded the Military Cross for his gallantry on this assault and for further distinguished activities in the rest of the campaign to liberate Europe. On D-Day it was calculated that Merlin sent nine encoded messages and another one the following day. On D+2 a further seven. On Day+4 and Day+5, the patrol sent fifty messages over the 48 hour period. On D+6 23 messages. All of these messages had to be verified and encoded before being sent by morse using the 22 set.

Appendix Z of the GHQ Regiment’s war diary.

Throughout the battle of Caen, Merlin Patrol was with 3 Canadian Division. On 12 July, Merlin went forward to 8 Canadian Brigade and Fulmar Patrol arrived with 2 Canadian Division.[1] On 17 July, Merlin joined 2 Canadian Division to report its battle. For Operation GOODWOOD (18 July) Merlin returned to 3 Canadian Division. Kite Patrol was with 2 Canadian Corps and Fulmar was with 2 Canadian Division. During Operation SPRING which commenced at 0330hrs on 22 July, Merlin, Fulmar and Kite remained with the Canadians. By 28 July, the rest of ‘B’ Squadron had arrived in Normandy. On 29 July, all B Squadron personnel reverted to B Squadron under command of 1 Canadian Army wef 2000hrs. By this time, this was the following situation:

Merlin 3 Canadian Division

Fulmar 2 Canadian Division

Kite 2 Canadian Corps

Harrier 1 British Corps

Gannet 51 Division

Eagle 3 British Division

Kestrel 49 Division

Merlin became a reserve at ‘B’ Squadron HQ and had truly been an efficient element of command and control for 3 Canadian Division.

Group photo of B Sqn HQ following Normandy campaign.

On 7 August 1944, Operation Totalize began at 2300hrs. Object to break through the enemy line on the axis road CAEN –FALAISE. The Deployment FCA Phantom on 7 August 1944:

Fulmar (Cohen)- 2 Canadian Infantry Division

Cormorant (Astor) +J3 to J, 2 Canadian Infantry Division

Gannet (Laurie) 51 Highland Division

Falcon +J2 to J, 51 Highland Division

Gull 4 Canadian Armoured Division

Skua +J1 to J Canadian Armoured Division

Eagle (Rosslyn) 3 Canadian Infantry Division

Kestrel 1 Polish Armoured Division

Tern Tac HQ 2 Canadian Corps

Merlin reserve at ‘B’ Squadron HQ.

On 8 August, Cormorant patrol switched to ‘J’ 3 Canadian Infantry Division. On 10 August, the operation was called off. ‘B’ Squadron patrols were resting at present locations between 11 and 12 August. Tern patrol sent to 49 Division midday 12 August for 48 hours. On 13 August, Pattrick attended a conference on Operation Tractable was held area Cormelles just South of Caen at 1400hrs. The following day Operation Tractable began at 1200hrs. All Phantom patrols faced danger in the battle for Normandy. Bombing of certain areas at H+2 by heavy bombers was part of plan, but small portion of own bombs dropped on own troops. Cormorant patrol received several near misses by nine feet. The patrol NCO Cpl Thomas was wounded with shrapnel in the leg and he was later evacuated. Tpr Minnis was also peppered with gravel but was reported to have been okay. Sigmn Ashton had a badly bruised leg and was replaced from SHQ by Sigmn Surridge. Two patrol motorcycles were written off. The patrol Jeep was slightly damaged and remainder of personnel were shaken and bruised. Nonetheless, the Patrol was operational again very quickly after events. Most patrols were in or near bombed areas.

Len Newman who served in Kite Patrol (NB Canadian insignia)

Lieut. Bryce was attached from ‘A’ Squadron with 7 Armoured Division. Lieut. Perret RAC posted to ‘B’ Squadron to replace Capt. Mainwaring. On 16 August, Skua was transferred to 51 Highland Division then to 7 Armoured Division to cover it with “J”. Tern replaced Gull at 4 Canadian Armoured Division. Gull returned to ‘B’ Squadron. On 17 August, Capt. Macmillan joined ‘B’ Squadron from RHQ in place of Capt Hon Astor. Went to RHQ to work with the Americans. Capt Macmillan was now in charge of Cormorant with J 3 attached. On 18 August Cormorant and J3 moved out to cover 4 Canadian Armoured Division. The Gannet patrol went to Liseux on 18 August and stayed in that area until the 23 August.

On 19 August, Some ‘B’ Squadron patrols bad on w/t all day almost certainly due to distance. The Squadron decided to send out the Astbury Booster set out permanently night and day. On 20 August, Gull replaced Kestrel at 1 Polish Armoured Division. Kestrel returned to ‘B’ Squadron HQ for a rest. Booster Set doing good well worth it. On 22 August, Gull moved to cover 6 Airborne Division in advance along coast. Between 22 and 25 August, there was no change in deployment in advance to River Seine. On 29 August, Falcon and J2 with Polish Detachment left 1 Polish Armoured Division and moved to Kite at 2 Canadian Corps where the Polish Detachment was dropped off. Falcon then took over from Cormorant at 4 Canadian Armoured Division and Cormorant returned to Kite at 2 Canadian Corps to rest and take over responsibility of Polish Detachment.

Conclusion

A new element had been introduced into the battlefield for the Canadian troops fighting in the Normandy battle. A liaison regiment was essential for Command and Control. First Canadian Army could be made aware about the progress of operations in other areas of the battle in Second Army and in their own area. Phantom officers liaising with Divisions at the frontline could easily send messages back to FCA by secure communication and trained personnel. During the battle, Merlin patrol was the first to keep HQ aware of the progress of operations. More patrols from ‘B’ Squadron joined ‘A’ Squadron in reporting the battle by intercept or liaison. Not all of these patrols worked with Canadians and have only focused on the relevant Canadian Corps and Division until FCA was ready. There are numerous records of Phantom and ‘J’ messages in the Intelligence Log at Second Army and this is probably the same in FCA.

Reference:

[1] WO 171/3459