Canada and RAF Bomber Command

The role of Canadian airmen in RAF Bomber Command during the Second World War was both significant and heroic, with nearly one-third of all personnel hailing from Canada. This substantial participation included service within 15 dedicated squadrons of No. 6 Group—exclusively a Canadian formation—as well as with various British and other Commonwealth squadrons. Over the course of the war, from 1940 to 1945, the harsh realities of air warfare were starkly highlighted by the loss of approximately 10,000 Canadian airmen, a testament to the high risks and sacrifices inherent in these critical air operations.

The strategic bombing campaign led by Bomber Command was a colossal Allied effort, demanding extensive material and industrial resources. The campaign aimed to erode German morale and capability through sustained aerial bombardment, contributing significantly to what was termed "enemy war weariness." Despite the intensive raids that resulted in the deaths of 600,000 civilians and left over five million people homeless, the expected collapse of German society did not materialize.

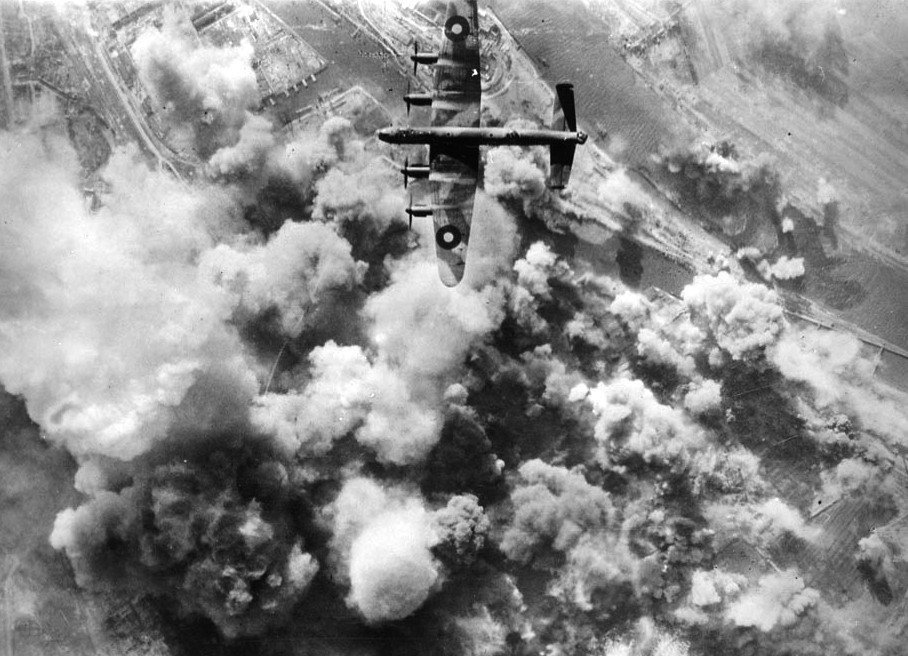

Among the notable tactics employed by Bomber Command was the implementation of "thousand bomber raids," a massive escalation in bombing efforts aimed at overwhelming German air defenses and infrastructure. The first of these raids took place on the night of May 30, 1942, targeting Cologne, Germany. The strategy was deemed successful in terms of damage and disruption caused, setting a precedent for future large-scale operations. These raids were among the most ambitious aerial operations of the war, designed to maximize impact on enemy capabilities while testing the limits of Allied air power and logistical coordination.

No. 6 Group

No. 6 Group of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) was officially formed on January 1, 1943. This formation was a significant part of the Canadianization policy, which sought to consolidate Canadian aircrew within their own national units under Canadian command. The establishment of No. 6 Group was not without controversy, involving disputes between high-ranking British and Canadian officers over the execution of the Canadianization efforts. These tensions reflected broader challenges in aligning national pride with operational integration during the Second World War.

Concerns about the quality of aircraft allocated to No. 6 Group became a significant point of contention among Canadian aircrew. Many felt that the RCAF squadrons were equipped with inferior aircraft compared to other RAF squadrons, particularly noting the assignment of older Wellington and Halifax bombers. These aircraft were seen as less capable and more vulnerable, which was believed to hamper the operational capability of No. 6 Group and contributed to lower morale among its aircrew. The initial decision to equip No. 6 Group with outdated Wellington and Halifax bombers was influenced by strategic decisions within RAF Bomber Command and the limited availability of more advanced aircraft like the Lancaster. This allocation not only impacted the group’s operational effectiveness but also underscored the logistical and strategic challenges faced by the RCAF in asserting its autonomy within the broader RAF structure. The use of these older bombers highlighted the difficulties of rapid squadron expansion and integration into the high-stakes bombing campaigns over Europe.

Lancaster “S for Smitty”.

Growing Pains

No. 6 Group experienced notably high loss rates during its initial operations, particularly among its less experienced crews. This high attrition was attributed in part to the group's use of older, less capable aircraft like the Wellington and Halifax bombers. The rapid expansion of squadrons and the initial equipment disadvantages contributed to operational challenges and heightened risks during missions. The struggle to improve aircraft quality and crew training was a significant focus for the group as it sought to reduce these losses and enhance its effectiveness in combat operations. Training and experience gaps were particularly pronounced in No. 6 Group, affecting its operational performance. Navigation errors and air discipline issues were notable among new navigators, who heavily depended on less effective navigational aids. The training programs initially failed to adequately prepare crews for the demanding conditions of wartime operations over Europe, leading to operational inefficiencies. Efforts to enhance training regimens and improve aircrew familiarity with their equipment and roles became crucial to overcoming these early challenges. Many Canadian aircrew members displayed a reluctance to transition from mixed RAF squadrons to all-Canadian units. The existing camaraderie and perceived expertise of their RAF colleagues made some Canadians hesitant to leave their units for newly formed Canadian squadrons.

No. 6 Group faced various operational challenges beyond aircraft quality, notably in the condition and suitability of their airbases. Initially, many of the airbases allocated to the group were not equipped with hard-surface runways, which are crucial for the operation of heavy bombers like the Halifax and Lancaster. This infrastructure deficiency not only impeded day-to-day operations but also heightened the risks associated with takeoff and landing, critical phases of each mission. The group had to prioritize significant upgrades to their bases to accommodate the demands of operating heavier aircraft and to align with the operational standards seen in other RAF units.

Despite its early struggles, No. 6 Group showed considerable improvement over time, achieving a performance level comparable to other RAF groups by late 1943. This turnaround was attributed to increased experience among the aircrews and adjustments in training and tactical approaches. The group's ability to overcome its initial setbacks demonstrated the resilience and adaptability of its personnel and leadership. By focusing on enhancing operational tactics and solidifying crew training, No. 6 Group was able to contribute effectively to the Allied bombing campaigns, gradually overcoming the challenges that had marred its initial operations.

Plotting Chart used by F/O Marvin Seale

An Example Bombing Raid

While there is no typical bombing mission, this schedule below is an example of how a bombing operation would have started.

A typical bombing raid during the Second World War followed a rigorous and meticulously planned routine.

The day would start early, with aircrews up by 7:00 AM, preparing for the long mission ahead. By mid-afternoon, the bombers were fully fuelled and ready for action.

At 11:00 AM, the crews gathered for a critical briefing where they received detailed instructions about the target, route, weather conditions, and potential enemy defenses.

By 4:00 PM, the aircrews were climbing aboard their aircraft, bracing for the mission as they made final checks on their equipment and instruments.

As dusk fell, the bombers took off, navigating under the cover of twilight to obscure their movements from enemy defenses. The bomb run itself occurred under the cloak of night, heightening the tension as crews relied on their training and each other to reach their targets and deliver their payloads accurately.

After the harrowing experience of dodging anti-aircraft fire and enemy fighters, the aircraft made their way back to base, where ground crews awaited to assess any damage and debrief the aircrews.

Each operation demanded precision and courage from all involved, encapsulating the harrowing yet routine nature of air warfare during the war.

The Chemnitz Operation

Map of Chemnitz

The bombing raid on Chemnitz on the night of March 5/6, 1945, was a crucial part of Operation Thunderclap, aimed at disorganizing German administrative capabilities and impacting their war infrastructure. The target was Chemnitz, a vital industrial hub described metaphorically as an 'octopus' with tentacles spreading into the surrounding valleys, symbolizing its extensive industrial and residential areas. The raid involved 185 aircraft from the Royal Canadian Air Force's No. 6 Group, which faced significant adversity due to harsh weather conditions. This led to high casualties, including the crash of seven Halifax bombers shortly after takeoff, marking it as one of the most severe non-combat losses for the RCAF.

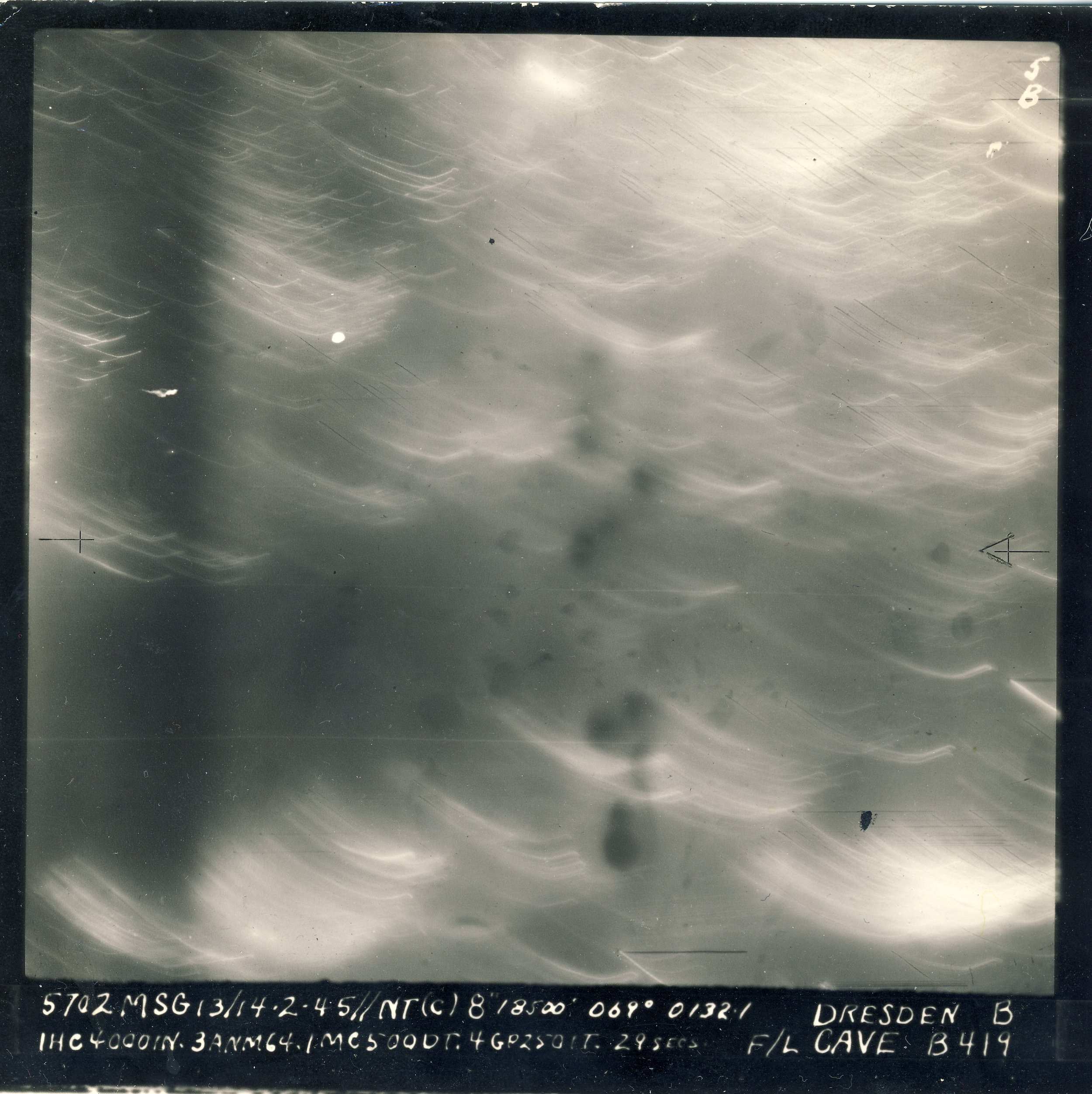

The strategic execution of the raid was meticulously planned. The Pathfinder Force led the operation, marking targets ahead of the main bomber force to maximize the impact of their payloads. Crews carried a mix of high-capacity bombs aiming to cause extensive damage to both the manufacturing capabilities and the railway network integral to Chemnitz. Despite the well-coordinated approach and the significant number of aircraft involved, the operation faced substantial challenges. Weather severely impacted visibility and navigation, complicating the bombers' ability to hit their designated targets accurately. Moreover, the defensive response from the ground, including flak and fighter interceptions, added further to the operational hurdles. In total 6-Group lost 17 aircraft. Six aircraft were shot down by the Nachtjagd and including 12 crashed in England and France, most presumed due to severe weather conditions

Flight Lieutenant Cave

Left to right: P/O Marvin Seale (Edmonton), Navigator; P/O Joe Ramsperger (Toronto), Bomb Aimer, W/O Ed Jones (Edmonton) Wireless Operator, F/L Harry Cave (centre), Sgt. Nick Horychka (Hamilton), Air Gunner and Sgt. Dave Stevenson (New Westminster) Air Gunner. From August-September-1944 F/Lt. Cave and his crew were posted to 1659 Heavy Conversion Unit at RAF Station Topcliffe for training on Halifax II and V aircraft. At Topcliffe, F/Sgt Walter “Jock” Smith (Glasgow), RAF, Flight Engineer, was added to the crew.

Harry Cave's journey with the Royal Canadian Air Force began on March 8, 1941. After completing his elementary flying training at Portage La Prairie in September 1941 and service flying training at Yorkton, Saskatchewan, he was commissioned as Pilot Officer in December 1941. Shortly thereafter, in January 1942, Pilot Officer Cave was sent overseas and attended No. 4 Flying Instructors School at Cambridge. Following this, he served as a flying instructor at No. 18 at Fairoaks and was briefly posted to 224 Squadron, RAF St. Eval, conducting a single operation with Coastal Command over the Bay of Biscay.

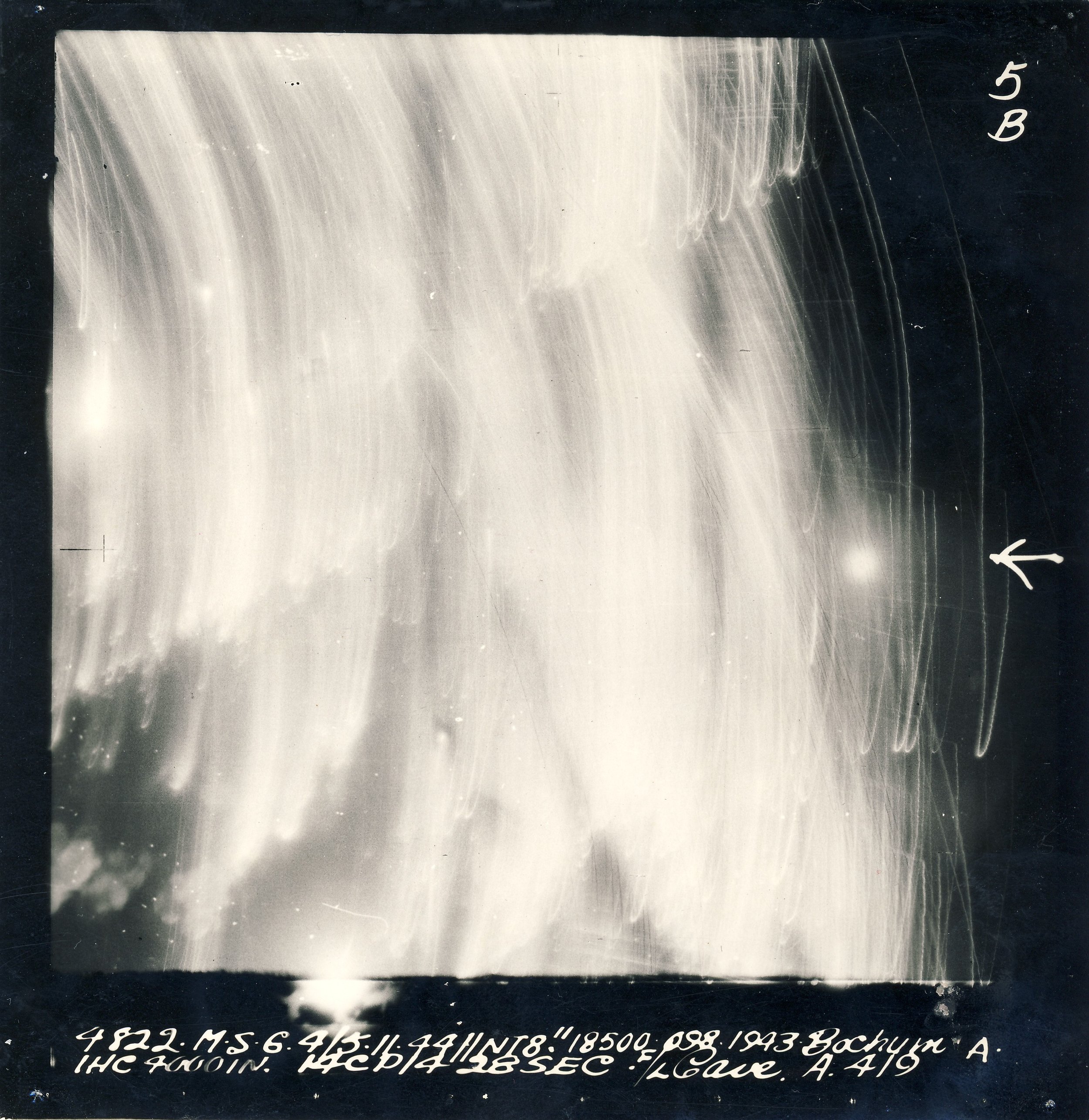

By July 1943, F/O Cave had earned his "A" Category as a flying instructor and by September 1943, he was instructing instructors how to instruct at No. 10 Flying Instructors School at RAF Station Woodley. His trajectory shifted significantly in January 1944 when he began training for Bomber Command with RCAF 6-Group. This included stints at No. 3 Advanced Flying Unit in South Cerney, Beam Approach Training at Cranage, and night flying instruction at Bibury. By mid-1944, he was at RAF Station Wellesbourne Mountford for operational training on Wellington bombers, alongside a newly formed crew. The crew transitioned through heavy conversion training on Halifax bombers at Topcliffe before being posted to RCAF 419 Squadron at Middleton St. George in September 1944.

At Middleton St. George, F/Lt Cave and his crew converted to Lancaster X aircraft, manufactured by Victory Aircraft in Malton, Ontario. Cave completed 30 operations, targeting strategic locations across Germany and one mission to Bergen, Norway. His notable operations included attacks on Duisburg, Bochum, Soest, Dresden, Pforzheim, Cologne, Chemnitz, Dessau, Essen, and Hannover. Following the Hannover mission in March 1945, F/Lt Cave and his crew were screened and repatriated to Canada in May 1945. Upon returning to civilian life, Harry Cave married Joan Louise Alderton and joined Stanley Brock Canada Limited. He later moved to Vancouver, BC, where he retired in 1975 and passed away in 1994.

Flight Lieutenant Cave Web Map

The 419 Squadron web map provides a dynamic visual representation of Flight Lieutenant Cave's 31 bombing operations over Germany aboard a Lancaster during 1944-1945. This interactive tool vividly animates each mission, tracing the flight paths taken to strategic targets like Bergen, Dresden, and Chemnitz. Users can explore detailed routes, view specific target locations, and gain insights into the tactical challenges faced during these critical sorties.

No. 6 Group Legacy

Reflecting on the history of No. 6 Group during the Second World War highlights the significant challenges and triumphs faced by these airmen. The transformation of No. 6 Group from its initial struggles with equipment and training to becoming a formidable force illustrates the strategic importance of adaptability and leadership in wartime. Moreover, their experiences underline the importance of strategic planning and operational execution in achieving military objectives, showcasing the vital role that Canadian forces played within the broader context of the Allied bombing campaign.

As we consider the legacy of No. 6 Group, it stands as a testament to the critical role of air power in modern warfare and the substantial contributions of Canadian airmen to the Allied efforts during the Second World War. Their story, marked by both adversity and accomplishment, contributes to our understanding of the war's vast operational scope and the integral part played by aircrews in shaping the conflict's outcome.

Sponsorship acknowledgement

Flight Lieutenant Harry Cave web map is proudly sponsored by Jim Cave, the son of Flight Lieutenant Cave. This sponsorship, in partnership with Project '44, is dedicated to commemorating and celebrating the distinguished wartime service of his father. This interactive map serves not only as a tribute to Flight Lieutenant Cave’s bravery but also as an educational resource that highlights the crucial role played by Canadian airmen in the Second World War.