Building an Air Force

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) was a collaborative scheme agreed upon in December 1939 between Great Britain, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Its mandate was to train Allied aircrew for the Second World War. Men from across the Commonwealth came to Canada to be certified in the positions of pilot, navigator, bomb aimer, wireless operator, air gunner, and flight engineer. Hosting this scheme was one of Canada’s greatest contributions to the war effort. Between 1940 and 1945, over 130,000 aircrew went through the BCATP, which led United States President Franklin Roosevelt to call Canada the “aerodrome of democracy”.

Canada and Great Britain had a history of air force collaboration, which began in the First World War. Regardless of airpower being a new military field, approximately 22,000 Canadians served with the Royal Flying Corps or the Royal Naval Air Service during the conflict. Not only could Canada provide a pool of recruits for the British, but also plenty of open space for them to learn their craft. Many of the Canadian recruits were trained on home soil before proceeding overseas. A partnership between (what was eventually titled) the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and the Royal Air Force (RAF) continued throughout the 1920s and 30s, although much scaled down.

A Staple in the Canadian War Effort

When the Second World War began in September 1939, the British Air Ministry was already planning for the manpower they would require in 1941 and 1942. Training aircrew was a lengthy process, especially for pilots, and so they had to think ahead. They were heavily counting on the Dominions (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa) to aid in filling these predicted quotas.

For the Canadian government, the beginning of the Second World War was plagued by fears of division between the country’s two major communities: Francophone and Anglophone. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King wanted to keep Canada’s war effort limited to avoid a repetition of the tensions of the First World War. He needed to convince English Canada that serious efforts were being made to support the British, while also assuring French Canada that conscription would be avoided at all costs.

Thus, the BCATP was a worthy solution. It would demand a major effort at home, stimulate the economy, and exert a significant influence on operations overseas, while also allowing for Canadian control of both the scheme itself and of its Canadian graduates.

The program accepted its first students on 29 April 1940 into No. 1 Initial Training School in Toronto. Subsequent schools opened across the nation as they were built. The BCATP’s goal was to be capable of turning out approximately 1500 aircrew every four weeks, or 19,500 a year, which would total to about 94,000 graduates. However, the key role played by Allied air forces throughout the war and high causality figures urged the scheme to greatly surpass these numbers. By 1945 over 130,000 aircrew had graduated from the BCATP, with 55% of those graduates being Canadian.

In addition to Commonwealth aircrew, there were also graduates from France (2000), Czechoslovakia (900), Norway (680), Poland (450), and the Netherlands and Belgium (450). It must be remembered that air force training had its risks, with over 800 BCATP students dying during training.

Cross-Country Mobilization

Visualization of what a day of flying might have looked like across Canada from every BCATP airfield.

Hosting the BCATP was truly a nation-wide effort. Personnel and experts across the country were mobilized in an unprecedented manner. In five years over 100 schools operated in all provinces except Newfoundland (which was not a part of Canada until 1949). Alberta, Saskatchewan, and southern Ontario were especially suitable for novice pilots due to their flat landscape, open skies, and generally clear weather.

Once the plan was publicly announced, towns and cities across Canada lobbied the federal government to be one of the chosen hosts. Local economies would benefit greatly from the increased population and activity that came with building, operating, and maintaining a BCATP school. This was especially important as the Canadian economy recovered from the Great Depression of the 1930s. In fact, the schools and airfields were staffed and operated by more than 104,000 Canadians, including thousands from the Women's Division of the RCAF.

Rural towns and cities suddenly had hundreds of BCATP staff and students who had money to spend and were looking for activities that differed from their wartime training. Local civilians took it upon themselves to entertain the newcomers by putting on recreational activities, inviting the trainees into their homes, and setting up entertainment centres. BCATP schools ran sports days, concerts, and wartime fundraising drives.

More then 3500 planes were used for BCATP including 2200 single seat aircraft such as the Tiger Moth, Finch, Harvard and Fairey Battle and 1300 twin engined Ansons

Training of aircrew never stopped, but requirements for which countries needed training and the type of training did.

The chart below explores different samples of training at different points of the war

End of the War

The BCATP was a success. By 1944 there were enough Allied aircrew who were either graduated or near graduation for the schools to begin to shut down. The program was completely finished by 31 March 1945. Host towns felt bittersweet during this transition, as the closing schools signalled the loss of a major economic boost, yet also the coming conclusion of the war. Some young women left their hometown to start a new life with men they had met during his training, while other young couples settled into the community they had met in.

The majority of the smaller BCATP schools had their infrastructure completely dismantled, dashing any local hopes for their own airport and a connection to the modern aviation industry. On the other hand, a decent number of BCATP schools near larger cities remained, transitioning into either RCAF bases or civilian airports. Thus, countless modern-day airstrips across the country owe their origins to the BCATP.

Course No.1, No.5 Operational Training Unit (Royal Canadian Airforce Schools and Training Units), Royal Canadian Air Force (R.C.A.F.), Boundary Bay, British Columbia, Canada, 9 June 1944

Robert Ridley was just 18 years old when he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force

You can follow Roberts journey through Flight Training and onto the war in Europe in our story map below.

Support the project:

How can you support the project:

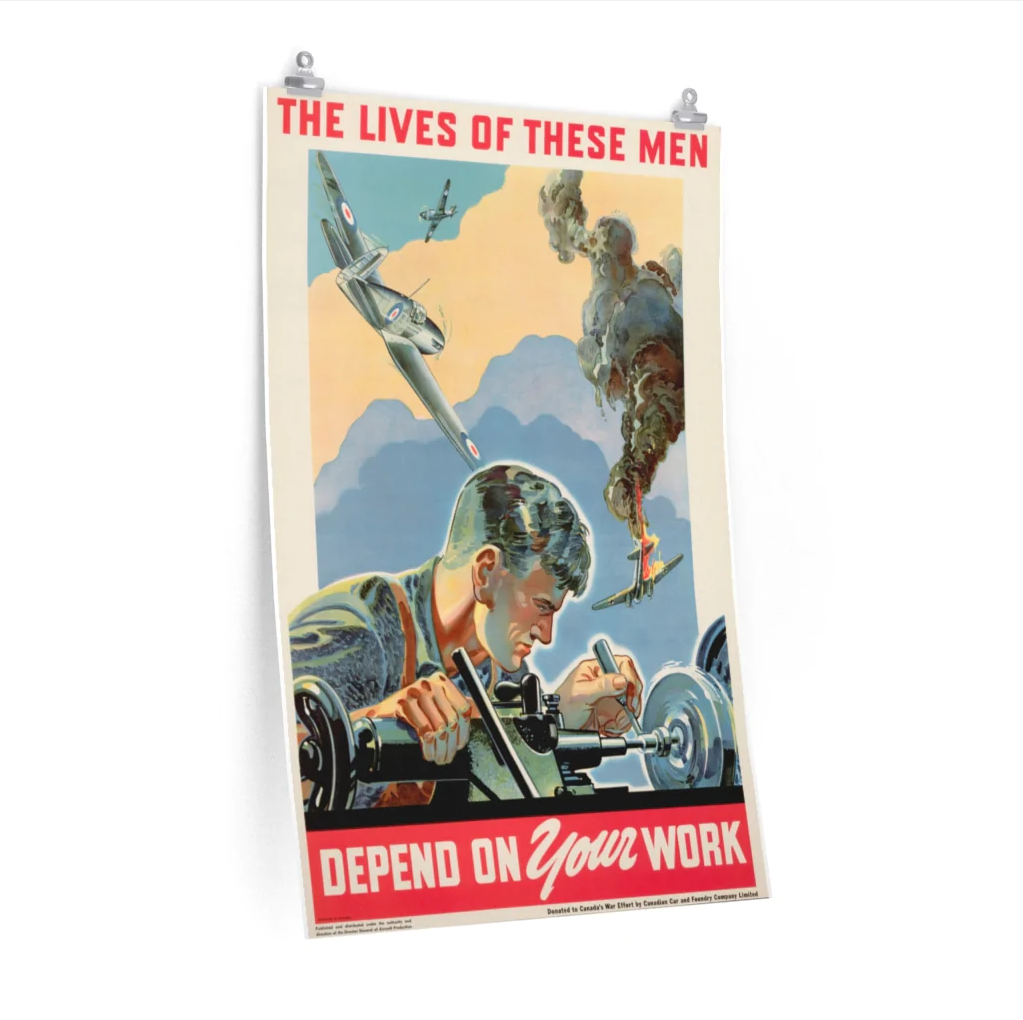

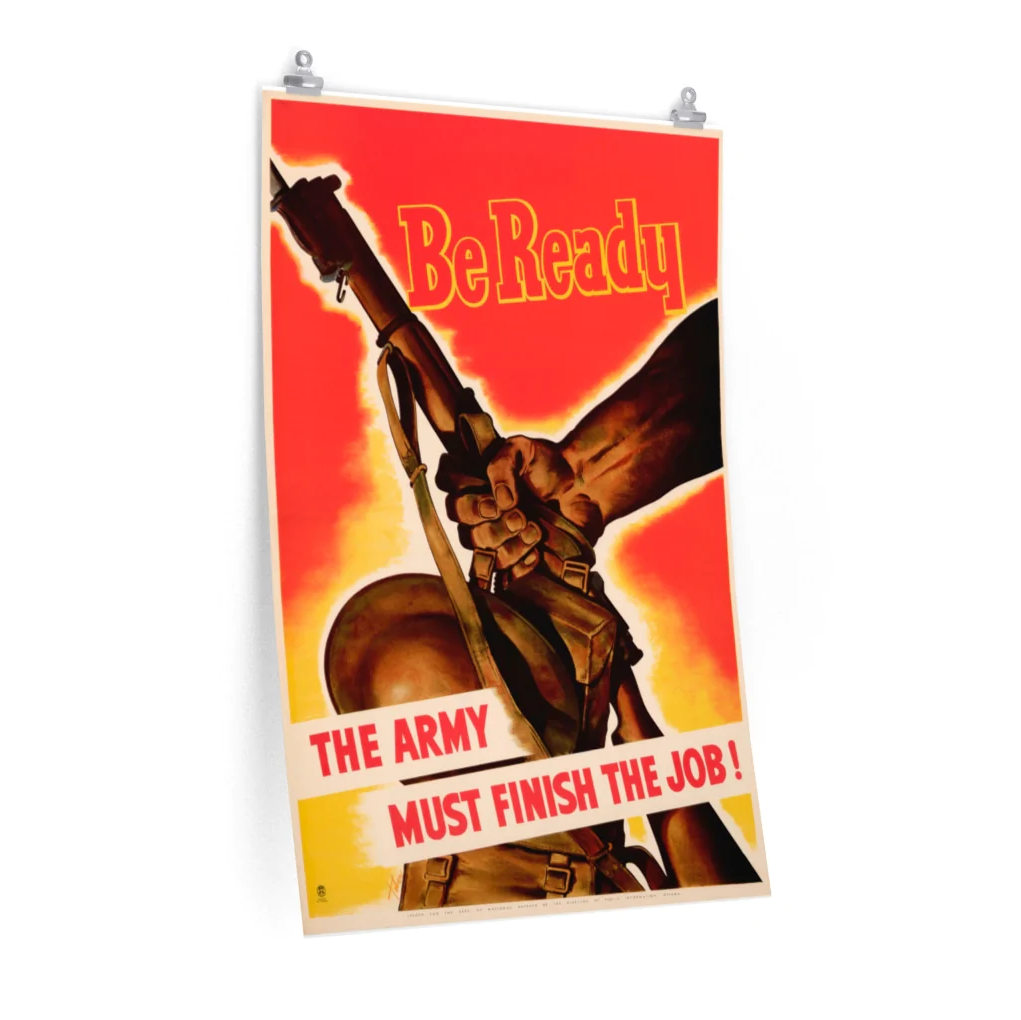

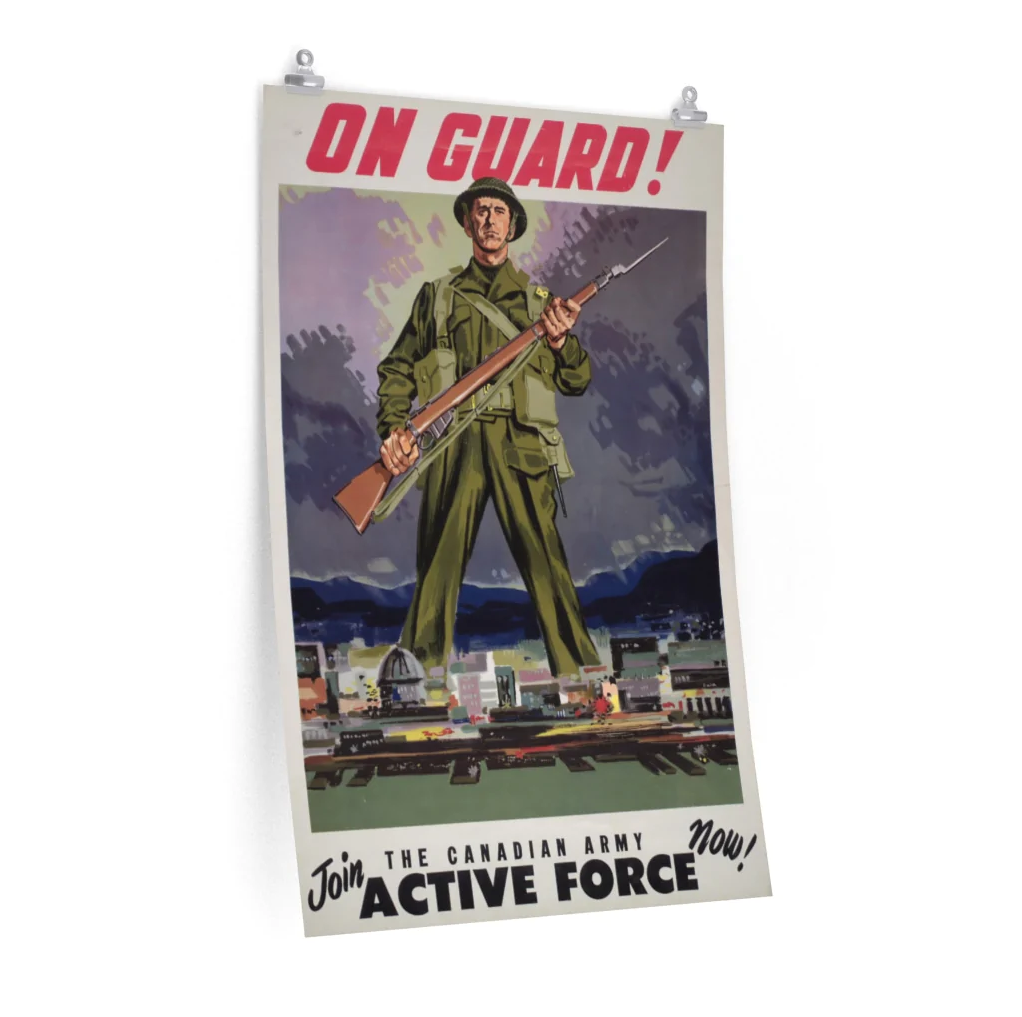

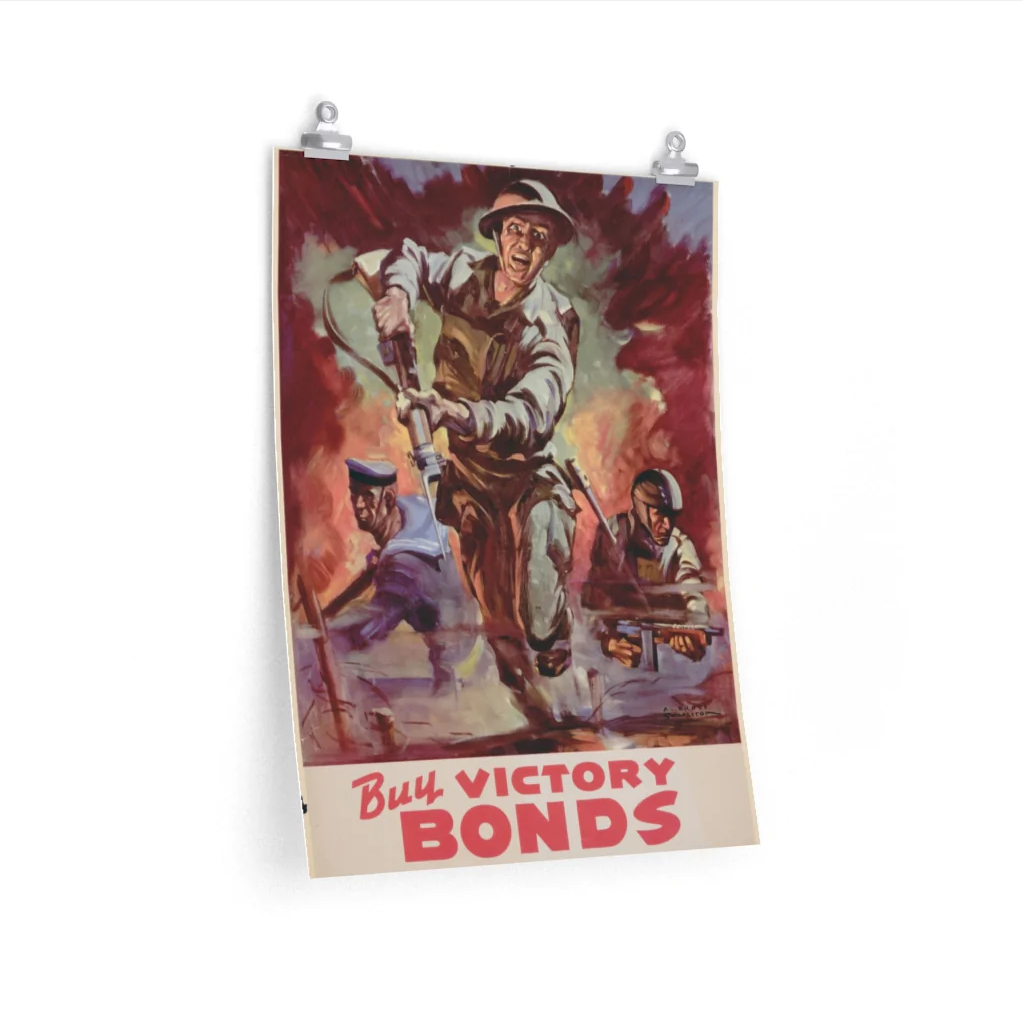

Buy a poster today!

We sell many authentic posters from the Second World War. These are high resolution scans of original posters that you can only find in the archives.

Each poster is printed on high quality paper ready for mounting in a frame for your office or living room.

The best part of buying a poster? 100% of proceeds are directed back to the project allowing us to continue to map out the Second World War.

Other ways to support the project:

Donate

You can help us tell the story of Canadian soldiers by donating today!

Our team is dedicated to keeping the story of Canada in the Second World War at the forefront using interactive technology that makes history open and accessible.

With your donation you help us to keep mapping and digitizing war diaries so we can continue to tell the story of those who served and those who fell.

Join Patreon

Do you want to become part of the team? Consider joining Patreon!

As a member of Patreon you can influence our project, what we are working on, and can even direct message our team. As a Patreon you can even get discounts to our entire store!

With your membership you can show your commitment to the project by helping us every month. And the best part is, every Patreon dollar goes directly to the web map!

![Non-commissioned officers of the Station Orderly Room [graphic material] : No. 2 Service Flying Training School, R.C.A.F., Uplands, Ontario, Canada, 1942](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b855caf3e2d09b204e7cad5/1671204396476-0I2UVICUTCUEHPPI5ZYM/9.jpg)