Right in Their Way

Major David Vivian Currie, VC and the Battle for St. Lambert-sur-Dives

By Alexander Fitzgerald-Black

Private Arthur Bridge and the rest of 14 Platoon watched with elation from the safety of their slit trenches as a flight of rocket-firing Typhoon fighter-bombers swooped in on a nearby crossroad. The Tiffies “operated very simply”, the foot soldier later reflected. “From their vantage point in the sky, they could spot their targets – trucks, tanks, wagons, men – and then dive towards them firing their cannons or rockets.”

After hours of watching their winged comrades meting out “death and destruction” to retreating German forces, one of the Typhoons took a hit from anti-aircraft fire. The pilot skillfully glided the plane into a nearby farmer’s field, where a haystack brought it to an abrupt, but safe, halt. Some of Bridge’s comrades leapt out of their slits and attended to the pilot, who insisted on surrendering. The soldiers had a laugh as they told the pilot – a Canadian from Winnipeg – that he was in friendly hands. The man was understandably nervous, believing he had been captured by the same troops he had been strafing moments before.[1]

CRMA Archive

Private Bridge and the rest of his unit, “C” Company, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, were dug in nearby, somewhere in the vicinity of Trun. This was their third week in the line. They had fought south from Caen towards Falaise in a pair of operations featuring massive armoured columns with infantry rolling forward in improvised armoured personnel carriers. These had been necessary to punch through well-prepared German defences featuring excellent fields of fire for machine guns, powerful anti-tank guns, and mortar and artillery observers. Now the German front had crumbled and Nazi forces were on the verge of encirclement. It was August 18th, and the bulk of German forces in Normandy were confined to a rectangle seven miles wide by six miles deep.[2]

With American armies to the south, British forces to the east and north, and Canadian and Polish troops pressing from the northwest, the Germans had just one escape route available to them. According to Canada’s best-known military historian, Tim Cook, the route lay “along the valley leading to the opening between Trun, St. Lambert-sur-Dives, and Chambois.”[3] Troops from the Lincoln and Welland Regiment had occupied the first town in the mid-afternoon, after a US Army Air Forces strike subsided.[4] The German escape routes through St. Lambert-sur-Dives and Chambois remained open.

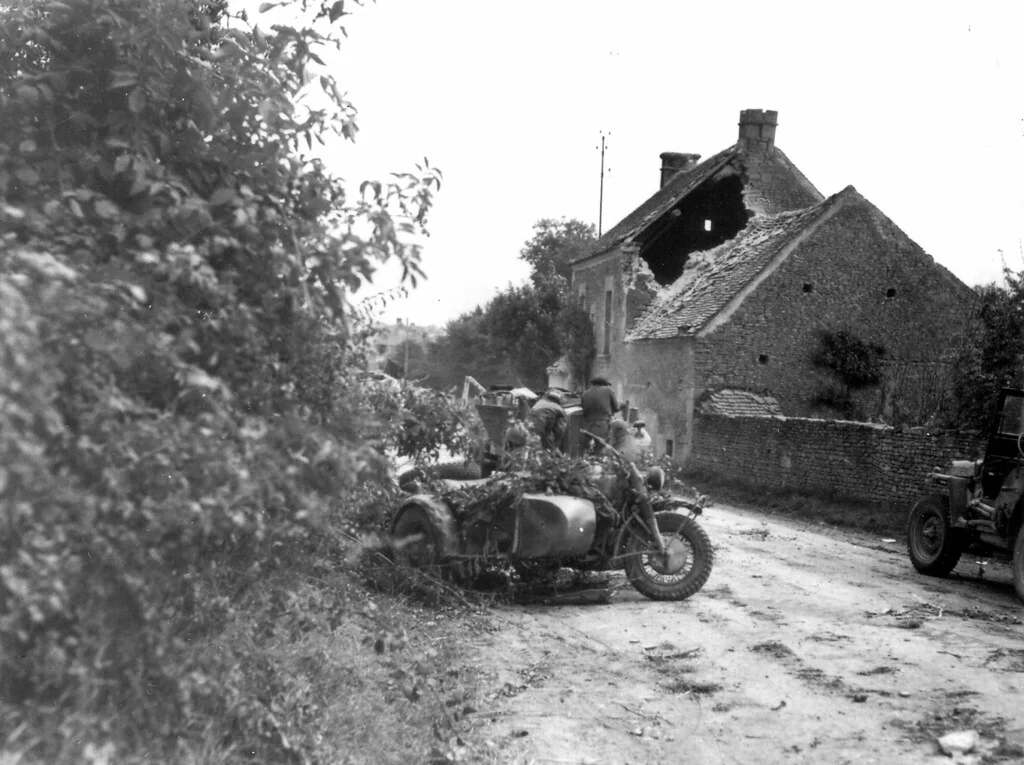

As Bridge’s unit settled into Trun for the night, a composite battlegroup under the command of Major David V. Currie approached St. Lambert-sur-Dives. St. Lambert was “a small village of typical Norman stone houses and out buildings on either side of the main road which runs about 400 yards from one end of the village to the other.”[5] Currie’s force consisted of 15 Sherman tanks of his own “C” Squadron, 29th Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (The South Alberta Regiment) and 55 men from the Argyll’s “B” Company.[6] Their orders were to push through St. Lambert and on to Chambois, sealing the German escape route, now known as the Falaise Gap. The Germans weren’t about to roll over, however. They fought with desperation to hold the shoulders of the gap open.

When Major Currie’s force approached the village, 88-mm guns knocked out two Sherman tanks. In response, “Currie immediately entered the village alone on foot at last light through the enemy outposts to reconnoitre the German defences and to extricate the crews of the disabled tanks, which he succeeded in doing in spite of heavy mortar fire.”[7] Faced with a village held in strength by infantry and anti-tank guns, Currie opted to wait for daylight before launching an assault. He positioned his force on a hill north of the village, Point 117. By midnight, the Regimental Headquarters (RHQ) Troop, under Lieutenant-Colonel Gordon D. Wotherspoon, and the balance of the regiment’s tanks joined Currie’s force on the hill.[8]

The next morning, Currie’s battlegroup moved out to assault St. Lambert. The RHQ Troop and “B” Squadron provided covering fire while “A” Squadron secured the force’s right flank and supply route back to Trun. At 0635 hours, Currie reported “attacking ROOSTER now.” The battle for St. Lambert was on. Sherman tank crews and Argyll soldiers managed to capture half of the village in the face of superior enemy numbers. Meanwhile, Wotherspoon ordered “B” Squadron to Point 124, to the northeast. These tanks would support the Poles as they drove for Chambois while harrying German forces using the local roads to escape.[9]

Word went up the line that the South Alberta’s would need further infantry support to hold their gains and manage their growing prisoner cages. Private Arthur Bridge and the Argylls’ “C” Company downed tots of army rum and fell in for the march through the fields and lanes between Trun and St. Lambert. They arrived to assist Currie’s battlegroup as darkness fell.

B company Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. LAC/DND/CRMA

The fighting had died down, so the company went forward through the village and towards Chambois. “Burning houses and vehicles that had been knocked out along the road” lit their path. A German machine gunner opened fire as the company approached Moissy, a hamlet about halfway to Chambois. With their company commander and others wounded, the unit returned to St. Lambert. They made their way back along a small lane where German tanks had parked for the night. “They didn’t cause us any trouble though,” Bridge recalled, “apparently thinking we were Germans too!” This incident illustrated the impossibility of keeping the enemy from infiltrating to freedom at night.

Reinforcements came from Bridge’s Argyll company, a company from the Lincoln & Welland Regiment, a Forward Observation Officer (FOO) from the 15th Field Regiment, and self-propelled 17-pounder guns from the 5th Anti-Tank Regiment, RCA.[10] Only part of this force reached Major Currie, who personally led “forty men forward into their positions and explained the importance of their task as a part of the defence.”[11]

29th Canadian Armoured Regiment and B company Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders LAC/DND/CRMA

The reinforcements arrived just in time. At 0800 hours on August 20th, the main German breakout attempt crashed into Canadian and Polish defences between Trun and Chambois. Private Bridge remembered that “there were thousands of Germans in various stages of organization and disorganization struggling to get through, and we were right in their way.”[12] Currie directed the defence both on the ground with the infantry and from the turret of his command tank. On one occasion he used a rifle to deal with snipers near his headquarters from the turret. On another he ordered the FOO to continue calling down medium artillery fire even though “short rounds were falling within fifteen yards of his own tank.”[13]

The Germans were desperate and they had numbers on their side. Currie later recalled one counterattack where the “Jerries came in so fast and thick that they climbed all over the tanks.” He continued, “The boys were fending them off with pistols, grenades and, in one instance, swinging the turret of the tank around to knock them off.”[14] As Currie’s position in the centre of the village became untenable, he ordered troops to concentrate on defending the northern end of St. Lambert.[15] Private Bridge was among those who dug slit trenches and held this new position, teaming up with a Bren gunner. “The attackers came charging on and were mowed down in their hundreds by the South Albertas’ tanks and our own machine gunners.”[16] Canadian tank crews who escaped their burning Shermans fought on foot with the infantry.[17] The battlegroup even freed a dozen American prisoners of war, gave them rifles, and put them into the line.[18]

The fighting continued overnight and into August 21st. “B” Squadron, surrounded at Point 124, fought its way back to Point 117. There, the RHQ Troop and “A” Squadron had held their ground the previous day against waves of German infantry intent on escape. The Germans left in the area had little fight left, however. By noon, “C” Squadron had sent 150 wounded and 700 unwounded prisoners of war to RHQ. The regiment tallied 200 wounded and 1,000 unwounded Germans captured for the day.[19] One Argyll soldier from “B” Company, Private Earl McAllister, captured between 50 and 150 prisoners of war single-handed.[20] The Canadian Army later credited Major Currie’s battlegroup with destroying seven German tanks, 12 88-mm guns, and 40 vehicles. They had killed 300 Germans, wounded 500, and captured 2,100.[21]

Currie’s battlegroup paid a heavy price for its stand. When the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders rallied their two companies in St. Lambert, they found just 70 men remained. The other thirty percent were casualties, including both company commanders. As for the village, it “became the symbol of the utter defeat and annihilation of the German Army,” according to one English correspondent. “The roads leading from the town were jammed with wrecked German vehicles; the ditches beside were lined with their dead; and the dirty, oily Dives River was swollen with wreckage and the bodies of horses and men.”[22]

King Tiger on the Falaise, Trun road. LAC/DND/CRMA

On a broader scale, the German Army suffered 10,000 killed and 50,000 captured in the final days of the battle.[23] Some had hoped for figures in the hundreds of thousands and historians have spilled plenty of ink arguing about who is to blame. Yet one distinguished historian of the German Army recently concluded that:

Discussing Falaise in terms of its failure to encircle the Germans fully – to emphasize what did not happen – obscures the enormity of what did happen. The Wehrmacht in the west suffered one of the most complete and destructive defeats in military history.[24]

Major David Currie’s battlegroup fought an incredible blocking action to put the finishing touches on this decisive victory.

In November 1944, Currie received the Victoria Cross, the British Commonwealth’s highest award for valour on the battlefield. Yet for Currie, “the honour belong[ed] to the regiment.”[25] In a wartime interview, the major cited the contributions of Lieutenant-Colonel Wotherspoon (who received a Distinguished Service Order for his role in the battle), the flank protecting squadrons, and the men in the battlegroup. After the war, Currie wrote that “The men had been asked to take on incredible odds, and while at times I am sure they were all afraid, I know I was, every last man did the job asked of him, without complaint.”[26]

Currie’s admission of fear showed a particular willingness to be vulnerable. He truly was the embodiment of the “reluctant temperate hero.”[27] The final word ought to be his:

There is little to be thankful for in war[.] I was thankful for one thing, as a result of the battle for St. Lambert[.] I know that there is much to fear in war, but to me, the greatest fear was the possibility that I might not measure up to that which was asked of me. St. Lambert proved to me that I could measure up, and left me with the certain conviction that the war with Germany was in its final stages and that we would be equal to the task ahead of us – the final defeat of Germany.[28]

Click on the image below and visit the beta web map

[1] Arthur Bridge, “In the Eye of the Storm: A Recollection of Three Days in the Falaise Gap, 19-21 August 1944,” Canadian Military History 9.3 (2000), pp.61-62.

[2] Robert M. Citino, The Wehrmacht’s Last Stand: The German Campaigns of 1944-1945 (University Press of Kansas, 2017), p.268.

[3] Tim Cook, Fight to the Finish: Canadians in the Second World War, Volume Two (Toronto: Allen Lane, 2015), p.269

[4] Terry Copp, Fields of Fire: The Canadians in Normandy (University of Toronto Press, 2007),

[5] Bridge, p.62.

[6] Angelo Caravaggio, “Commanding the Green Centre Line in Normandy: A Case Study of Division Command in the Second World War,” PhD dissertation, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2009), p.307.

[7] Victoria Cross Citation of David Vivian Currie, The London Gazette, supplement No. 36812 (27 November 1944), p.5433.

[8] Library and Archives Canada (LAC), RG 24-C-3 Volume 14295, The 29th Canadian Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (South Alberta Regiment) War Diary, 18 August 1944.

[9] Caravaggio, p.309.

[10] Copp, p.246.

[11] Victoria Cross Citation of David Vivian Currie, p.5433.

[12] Bridge, p.65.

[13] Victoria Cross Citation of David Vivian Currie, p.5433.

[14] “Major David Currie Battles in Normandy, Wins the Victoria Cross,” CBC Radio News, 16 December 1944, CBC Digital Archives, https://www.cbc.ca/archives/entry/1944-major-david-currie-battles-in-normandy-wins-vc.

[15] Caravaggio, p.321.

[16] Bridge, p.65.

[17] Directorate of History and Heritage, Ottenbreit citation)

[18] LAC, RG 24-C-3 Volume 14295, The 29th Canadian Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (South Alberta Regiment) War Diary, 20 August 1944.

[19] Ibid., 20 to 21 August 1944.

[20] The Argyll’s War Diary entry (see citation below) for 21 August 1944 provides the higher figure while Arthur Bridge recalls the lower figure (see p.67 of his account).

[21] Victoria Cross Citation of David Vivian Currie, p.5433.

[22] LAC, RG-24-C-3 Volumes 15026 and 15027, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada War Diary, 21 August 1944.

[23] Jonathan Fennell, Fighting the People’s War: The British and Commonwealth Armies in the Second World War (Cambridge University Press, 2019), p.549.

[24] Citino, p.268.

[25] “Major David Currie Battles in Normandy, Wins the Victoria Cross,” CBC Digital Archives, https://www.cbc.ca/archives/entry/1944-major-david-currie-battles-in-normandy-wins-vc.

[26] David V. Currie, “St. Lambert-sur-Dives,” The Canadian Research and Mapping Association collection.

[27] Geoffrey Hayes, Crerar’s Lieutenants: Inventing the Canadian Junior Army Officer, 1939-45 (Toronto: UBC Press, 2017), p.189.

[28] David V. Currie, “St. Lambert-sur-Dives.”