“The Greatest Obstacle to Our Success”

“The Greatest Obstacle to Our Success”

By Dan Moden

A dark overcast sky looms overhead; the low rumble of engines and waves filling the air between the nervous-silence that envelop the crews. Miles behind them, the massive invasion force slowly steams towards France. Onboard their Bangor-class minesweeper vessels, the men of the Royal Canadian Navy know their objective is but one of many critical tasks necessary for the success of Operation NEPTUNE. It is perhaps the most critical task, yet it remains one of the unheralded acts of bravery and naval discipline in the Second World War. Sailing for hours under darkness without escort or air cover, these men (along with hundreds more sailing astride them) worked tirelessly to clear the proverbial runway to the beaches of Normandy. If they are detected, they are on their own. If fired upon, “straight ahead” was the order. Success means the first steps into Europe. Failure means destruction. The men of the 31st Canadian Minesweeping Flotilla knew their role was important but could not possibly foresee the historical significance of their accomplishments, nor the brutality that would proceed their work. Nevertheless, they cleared Approach Lane 3 towards beach sectors Charlie, Dog, Easy and Fox, better known by their collective codename: Omaha.

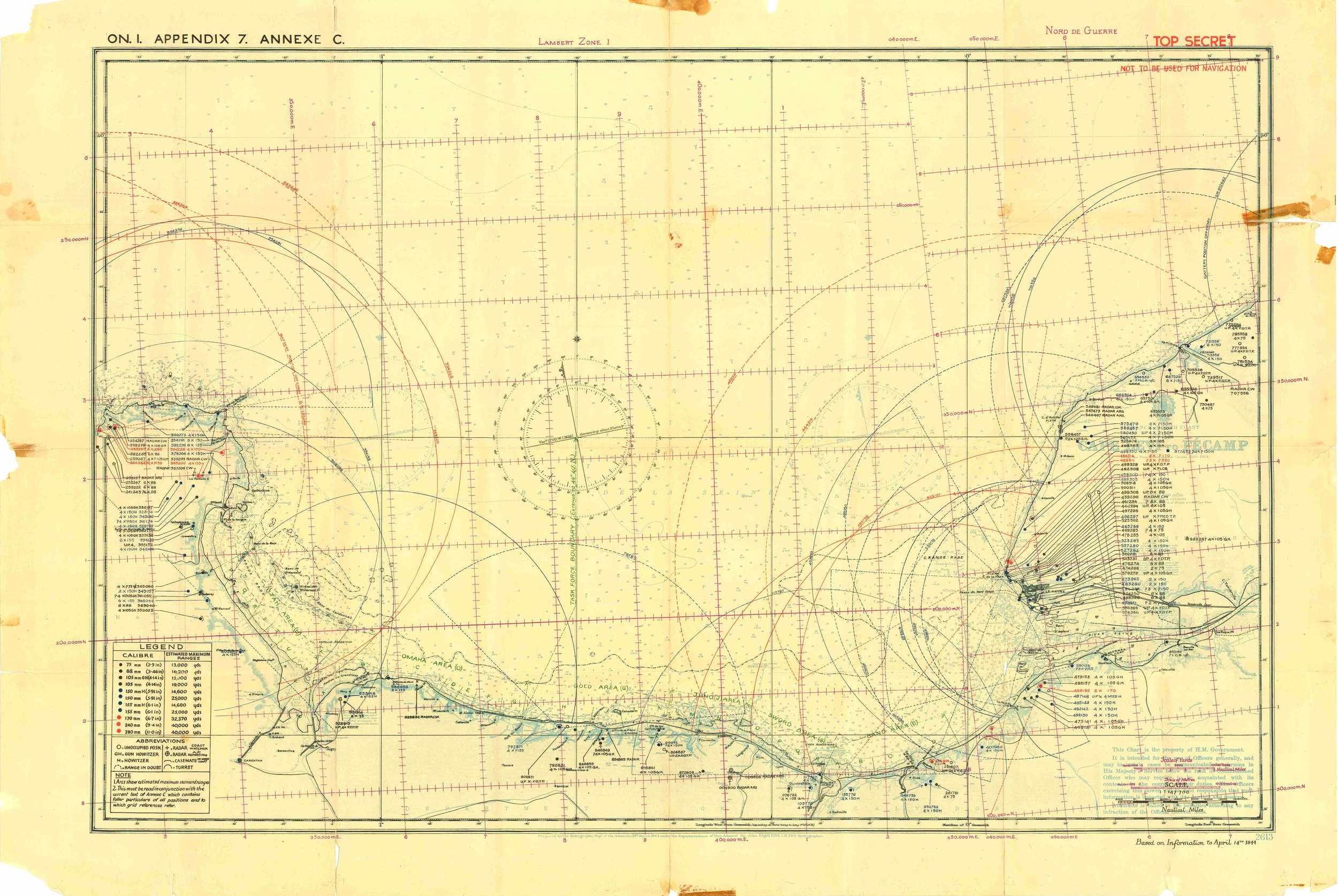

Chart of Coastal gun positions and emplacements on the Normandy coast. Courtesy of CFB Esquimalt Naval & Military Museums.

I’ve had the pleasure of being a part of the CRMA and working on Project ‘44 for over a year now, and in that time I have come to notice countless aspects and complexities of the Normandy campaign that I simply did not recognize until looking at it through this particular lens. Stories like that of the 31st Canadian Minesweeping Flotilla were left unseen by myself until diving into this project. Even as a military enthusiast, I was learning new stories of the campaign with every day of research. Recently I’ve been researching the naval aspect of Canada’s Normandy campaign, and I have gained a new level of appreciation for Operation NEPTUNE and the staggering level of planning it required. Logistically speaking, Operation NEPTUNE was nothing short of a tremendous triumph for the Allies. To transport over 150,000 men, on nearly 7000 ships and small vessels, all of which require an endless amount of supplies to fight through a defense network spanning the entire Atlantic coast, remains astonishing. The War Diaries procured and digitized by the CRMA often express the awe-inducing sight of the invasion force assembling in Southern England. An incredible document detailing Force J (the British/Canadian assault force headed for Juno Beach) by Lt (Ret) Barry Miller, CME, and his associates at WW2talk pointed me in the right direction for the authentic primary sources detailing NEPTUNE.

(As an aside, I cannot stress how informative this document was and how exhausting the research put into it must have been. An incredible job by Lt Miller and those members of WW2Talk who contributed to the document. It is absolutely worth a look if you have any interest in NEPTUNE and seeing the full scope of Force J’s complexity.)

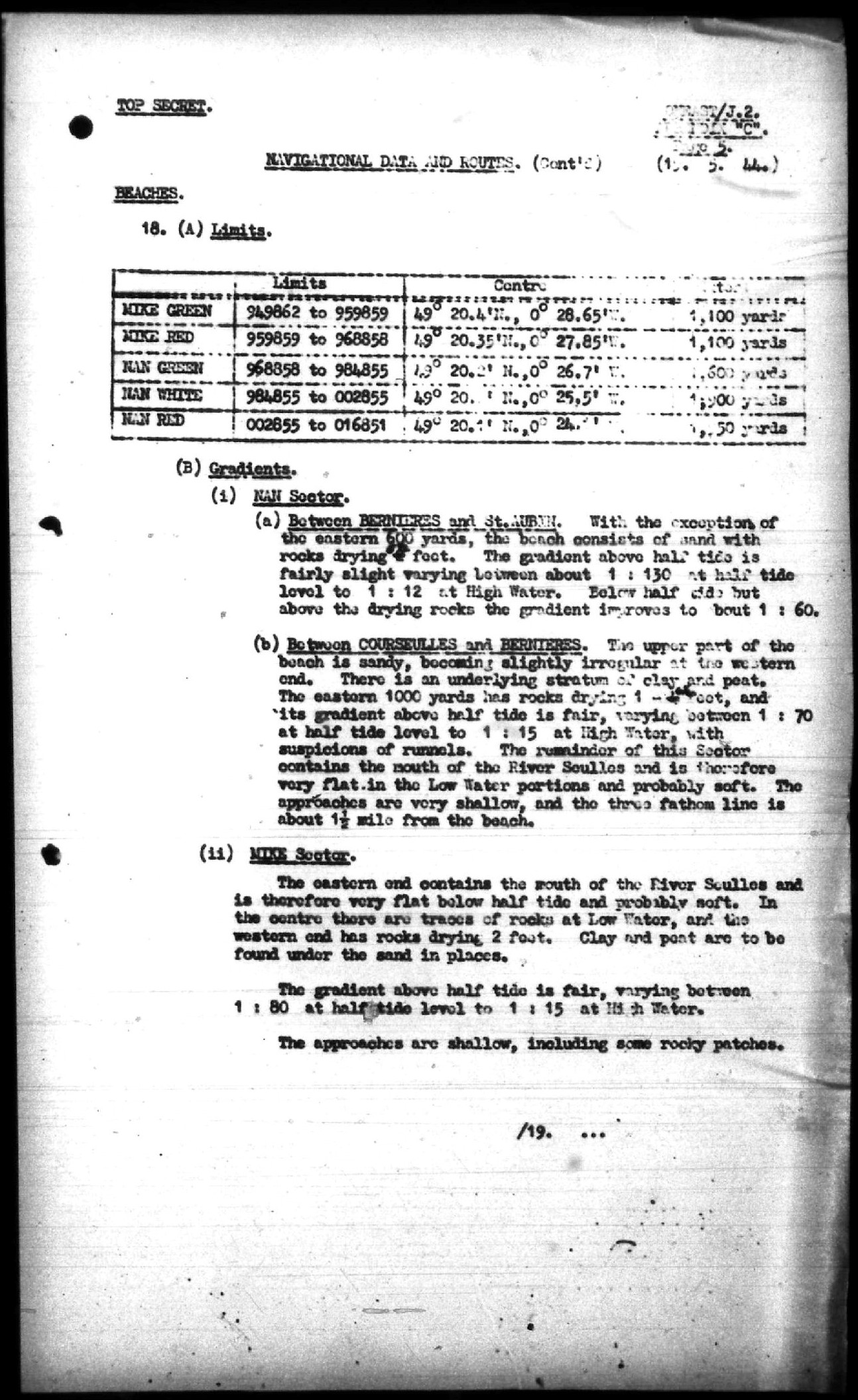

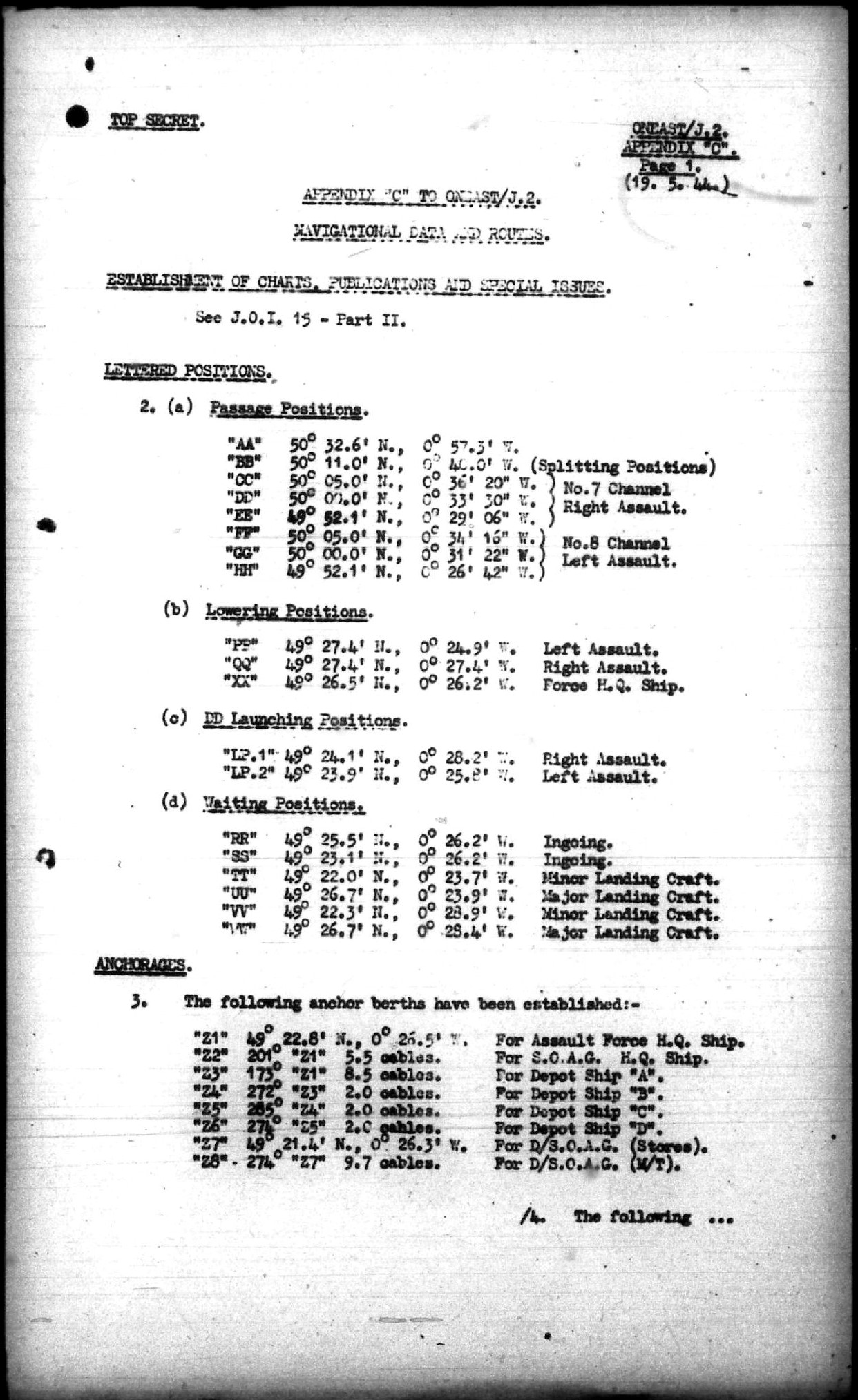

LMA mine

Following the sources found in Lt Miller’s document, I ventured to Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa with a specific task: find the authentic NEPTUNE plans. What I found was astounding. Landing tables, unit-ship allocations, a minute-by-minute timeline of when/where each assault craft would (theoretically) land, maps detailing the individual routes between England and Normandy, among much more. Through the fantastic Fold3 online resource, I was able to find the complete Operational Orders for NEPTUNE. This document, which includes all intelligence, maps, planning, logistics and subsequent Operations within NEPTUNE, is over 3500 pages long. Clearly, you can see why the planning for the invasion took over a year. It was eye-opening to see the effort put forward to both protect and adequately prepare the men for the operation. What excites me most is the potential within these documents for re-telling the story of NEPTUNE from a Canadian perspective. There is a massive database awaiting creation that links regiments to their serials, serials to their landing ships, ships to their beaches, and the timing of their individual beach landings. This is why we created Project ‘44: to bring these moments back to the public eye and show Canada the realities of OVERLORD. Creating that three-dimensional story of the Normandy campaign would be incomplete without linking the naval component to Project ‘44, and this is how it can be done.

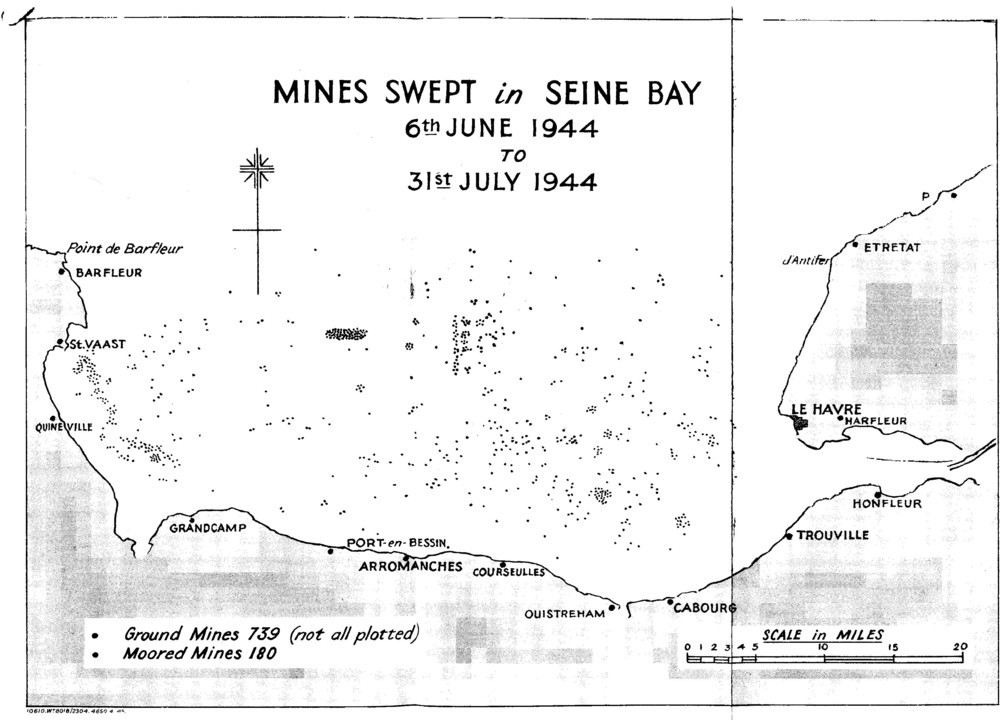

As is the case with the aerial and regimental aspects of campaign, the Canadian naval perspective brings its own history and stories that deserve re-telling. Leading up to the commencement of OVERLORD, the Royal Canadian Navy was primarily tasked with escorting merchant fleets across the Atlantic. Canadian naval officers continually sought further autonomy from the Royal Navy, desiring more vessels and more convoys with entirely Canadian crews. Over time, they were given the responsibility they craved. Canadian escort groups, destroyer flotillas, and minesweeper groups composed of (mostly) RCN vessels and staff became increasingly common. Having built up its Naval capacity since the beginning of the war, the RCN had a sizeable number of small vessels enrolled in NEPTUNE preparations. Much like the Canadian infantry and armoured brigades going ashore, the role of the RCN would be understated yet vital to the overall operational success. They were ordered to bring 16 Bangor-class minesweepers to aid in sweeping the passage between England and France. Of those 16 RCN ships, ten were composed into their own flotilla while the rest were dispersed to various Royal Navy flotillas. From the night of June 5th until the arrival of the main fleet on D-Day, the minesweepers worked to clear their respective lanes and the anchorage bay around Normandy. The success of NEPTUNE (and indeed OVERLORD) depended on these small ships to rid the approach lanes of the vast number of mines laid by the German defenders. I know I personally have failed to recognize the true danger the mines posed to NEPTUNE, and I believe the average person would likely say the same. Luckily for those men crossing the Channel, Supreme Allied Command did not underestimate their threat. It was Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, Allied Naval Commander for NEPTUNE, who put it best when he wrote: “There is no doubt that the mine is the greatest obstacle to success.” To clear that obstacle, the minesweeping flotillas were launched and Operation NEPTUNE took its first steps towards Europe.

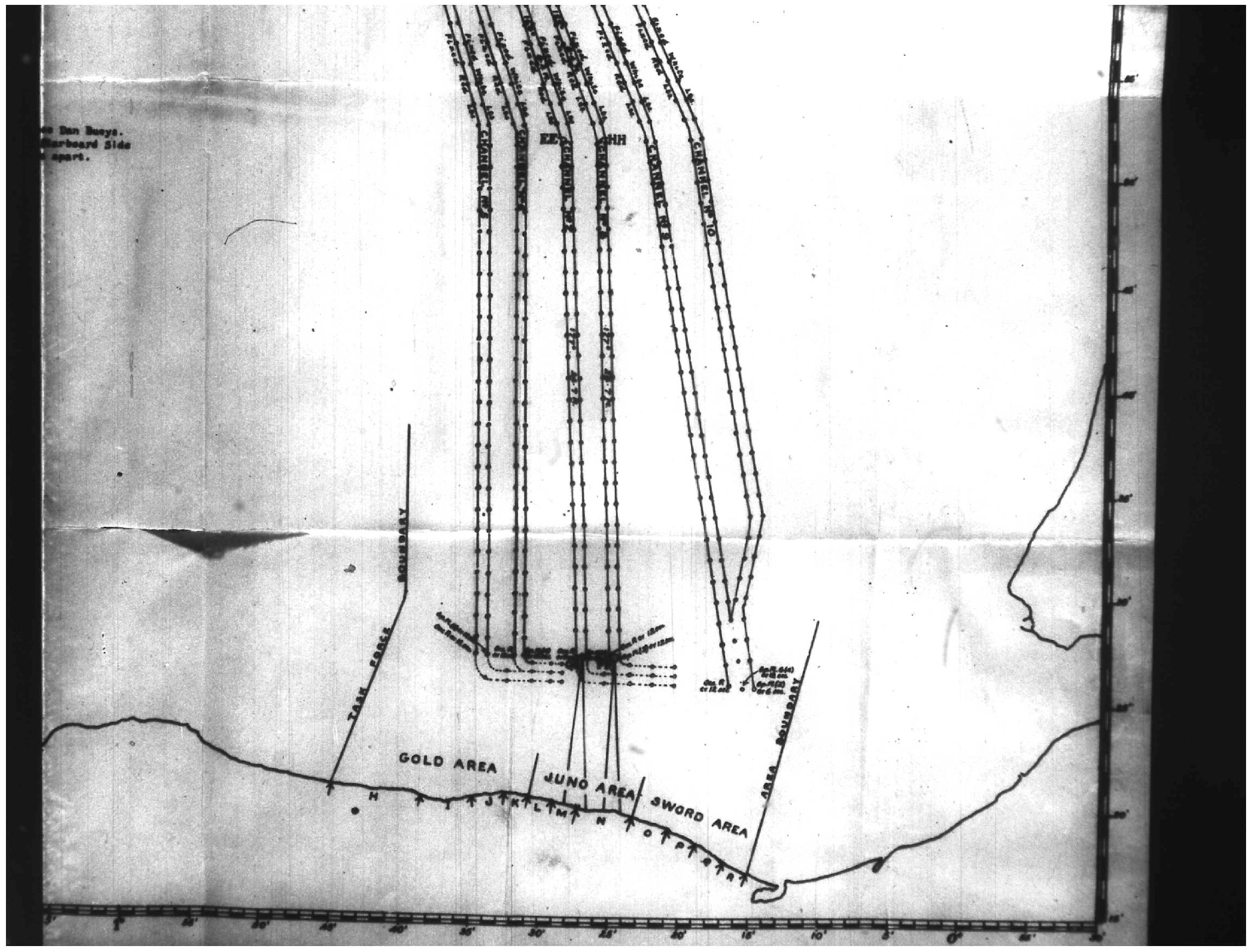

German sea mine

Do you know where Supreme Allied Commander Eisenhower was on June 5th, 1944? Likely not. He was in Portland, England, personally delivering his orders to the hundreds of minesweeping sailors before their departure to France. That alone should tell you about the importance of their task. The RCN minesweeping flotilla (then designated as the 31st Canadian Minesweeping Flotilla) would depart from Portland early on the 5th to begin their mission. They first headed to Area Z, Southeast of the Isle of Wight and lovingly referred to as “Piccadilly Circus.” This would be the Rendezvous Point through which every ship of NEPTUNE would pass before turning South to Normandy. Lane 3 was the designated approach for the 31st, and much to the dismay of its Canadian crews, that lane was earmarked not for Juno Beach but for the assault on Omaha Beach by the 29th and 1st US Infantry Divisions along with nine US Rangers Companies. The flotilla began their southward sweep around 5:30pm on the 5th, led by Commander AHG Storrs aboard the HMCS Caraquet. They advanced in their diagonal “G” formation (much like snowplows clearing a major highway) and were directed to keep their line even if engaged by the enemy. Navigation had to be perfect amidst the chaotic waters, requiring constant concentration. Along with nine other flotillas, the 31st spent nearly 12 nerve-wracking hours clearing every mine out of their respective approach lane before sweeping the areas designated for lowering landing craft and fire support ships. Dimly-lit buoys were laid behind flotillas to mark the paths for the invasion force. Mines were either detonated underwater or were forced to the surface, but they could not be detonated once surfaced for fear of alerting the German defenders (they instead let the mines float out of the lanes lest they pose immediate danger). The final hours were spent excruciatingly close to the coastal defenses, as close as one and half kilometres at times, and detection would’ve been met with furious bombardment from the Germans. Make no mistake, the job was treacherous. The Allied plan for NEPTUNE expected the vessels to be detected and fired upon, and heavy casualties (as high as “two-thirds”) were seen as a necessary cost.

Bangor minesweeper

Order of images: HMCS Caraquet, HMCS Vegreville, Landing Ship, Landing fleet.

But no bombardment came. On June 6th, without a single minesweeper lost, the main armada came into view as the sun rose in the early morning hours, and only then did the German guns finally open up. As the 31st flotilla continued sweeping throughout the Seine Bay, they became witness to one of the most gruesome battles of the entire Western Front at Omaha Beach. To get a first-hand account of their experience, Veterans Affairs Canada created a series of videos with a Mr. Gray, an RCN sailor aboard the minesweeper HMCS Vegreville of the 31st Flotilla. His descriptions of their journey to France depict the brutality seen on the beaches. In Mr. Gray’s words:

“As soon as that ramp come down from the thing there, them poor devils went ashore, there. They were brave men. If there is any such a thing as a hero on D-Day, it was the first assault troops that went ashore because they landed there. They were in no man’s land. They had nowhere to go.”

By the end of June, over 250 mines had been swept by the minesweepers, with approximately 100 being removed by RCN vessels. The exemplary work of the 31st Flotilla garnered praise throughout the Allied channels, and Commander Storrs was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the American Legion of Merit for his work clearing the approach to Omaha. Yet, as commendable as their work was, the work of the men ashore was the story of the day and became the focal point of the war. It is more than understandable why the battles along the beaches of Normandy have resonated through society even up to this day, but we should never forget the work of those small sloops and trawlers, no matter how “insignificant” their contribution is perceived.

With the sheer amount of planning and coordination for NEPTUNE came a massive volume of documents, preserved but stashed away. The challenge for us at the Canadian Research and Mapping Association is finding these documents and bringing them back to the public light. The research on these documents has made me realize the naval aspect of Canadians in Normandy deserves greater commemoration. Mapping out the progress of every regiment and/or ship in the days leading up to June 6th is a real possibility. This doesn’t have to end with NEPTUNE’s conclusion either, as the fight along the French coast for naval supremacy did not stop once those soldiers were in Europe. The continued success of OVERLORD required a commitment from the RCN to defend the supply fleet in their travels, support the infantry where possible, and destroy enemy vessels along and below the surface. The information is all there, the history is in front of us. Now we aim to show the Canadian public the depth of the immense task those men faced head-on in 1944.