Sgt Moe Hurwitz - Part 2: Some Never Die

Some Never Die

By authour David O’Keefe

Moe made his long-awaited combat debut on August 8th 1944, in Operation Totalize – the largest operation yet undertaken by the Canadian Army in the European war. The Grenadier Guards' role was straightforward but far from simple. All three squadrons of Sherman tanks would take part in the breakthrough of the heavily defended German line south of Verrières Ridge, near a dominating height known as the Cramesnil Spur that overlooked the hotly contested road to Falaise.

Moving in the darkness, shrouded with the smoke of burning German vehicles and clouds of dust churned up by the advance of thousands of Allied vehicles, the going for Moe in his tank, christened "Geraldine", proved slow and arduous. By the time the lead elements reached the town of Cintheaux near dawn, stiffening German resistance had threatened to crush any momentum in the Canadian advance built up during the night. With any thoughts of bypassing the town now out of the question, the Guards received orders to pounce just before first light with one squadron attacking from the east of the German position, which ended in frustration and heavy casualties. A second attack from the same flank later that afternoon also took a heavy beating from the ever-thickening German anti-tank screen comprised primarily of deadly 88mm anti-tank guns, supported by anti-aircraft guns and German tank-hunting teams.

By 16:00 hours, fears within Canadian high command that Totalize might sputter and stall turned to desperation. With the success of the advance hanging in the balance, Moe's Troop of tanks (under the command of then- Lt. Ivan Phelan) received orders to launch an attack – this time from the west - and to do so "at all costs."

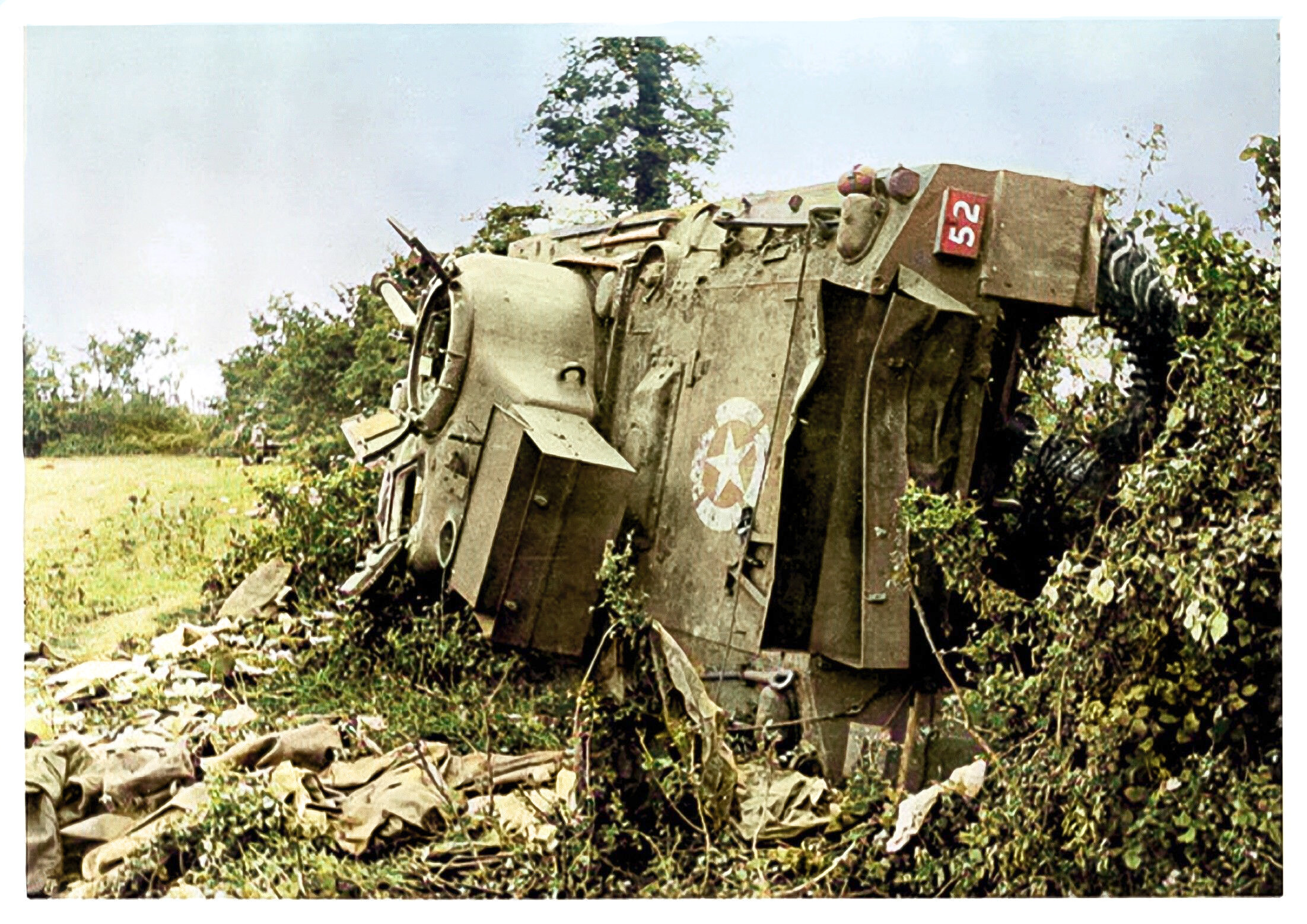

Sherman tanks from 4th Armoured Division on the move near Cintheaux, France during Operation Totalize. (Library and Archives Canada PA140822)

Moving in diamond formation with Moe on the right flank, the troop of Sherman tanks launched its assault by slipping out into no man's land through the positions of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada tasked with providing covering fire for the attack. The skilled German gunners waited until the tanks had moved out into the open field before letting loose with armour-piercing shot from their panzer and anti-tank guns. With only one option – to charge ahead – Moe’s troop returned fire with machine-guns and high explosive rounds from their main guns. In this miraculously “brief, brilliant and decisive action,” which Phelan coined the “fast dash,” the Guards penetrated the German position knocking out eleven tank destroyers and anti-tank guns in the process without suffering a casualty.

Now came a most awkward and pregnant pause, as the Guards found themselves amongst the enemy position without infantry support. Immediately, Phelan noticed upwards of thirty German infantrymen shaking off the initial shock and bewilderment of the audacious attack and frantically contemplating their next move.

As Phelan noted, it was a "tense situation," for his Shermans now lay at the mercy of the enemy’s hand-held anti-tank rockets and magnetic mines. Always impatient with indecision, Moe did not wait. Before the Germans could gather their wits, rally, and mount a counterattack, he bolted from the turret of his tank and seized the initiative.

"Like a flash," Phelan recalled, Moe "leapt out of his tank, Sten (submachine-gun) in hand, and with a mighty shout" dashed "up and down the hedge rooting prisoners out of their slit trenches."

But before he could finish, the ammunition tucked inside a burning German tank destroyer ignited. In the "terrible explosion" that followed, one Guardsman fell - killed outright - with five others wounded, including Moe.

Burned out Sherman Tank

Pinned under a fallen tree branch and suffering light burns to his legs, Moe feared the Germans would use the twist in fate to turn the tables on his men. Working his way from under the weighty bough he rose, still "dazed by shock,” his “hair and moustache singed” and "one arm numb from the impact of the tree,” grabbed his Sten, and continued the round-up of his German quarry.

As Phelan recalled, “Moe was a fierce-looking individual at the best of times with his heavy black brows, square chin, and big hands. With his moustache, he was truly formidable, and just his appearance would induce some Germans to croak in a fear-stricken ‘Kamerad!’ when he approached.”

By the time the Argylls arrived on the scene to consolidate the hard-won position, Moe’s quick thinking and decisive action carried out with “icy deliberation” led to the capture of over thirty prisoners and snuffed out any desire in the enemy to continue the fight.

The heroic acts of Moe and the rest of his troop played no small role in the capture of the town of Cintheaux and served as the first example of his "vital leadership" and "offensive spirit" that the Guards would come to know over the next few months.

In recognition of their actions on August 8, Phelan received the Military Cross while Moe was promoted to Troop leader and given command of a Troop of four Sherman tanks, and awarded the Military Medal for “acts of gallantry and devotion to duty under fire."

Over the next six weeks, more hard-driving combat followed as the Canadian Army pushed up the “long left flank” of the Allied drive towards Hitler’s Third Reich after the German Army had collapsed in Normandy at the end of August.

By late September 1944, the Grenadier Guards found themselves embroiled in a series of battles in the Scheldt, an unforgiving slice of Dutch soil that controlled the approaches to the massive port of Antwerp much needed to support the Allied armies in Europe.

Despite an unprecedented string of Allied victories, stress and strain of constant combat had begun to take its toll on the men. But as Lt. Phelan recorded, Moe had stood out as "the powerhouse he always was in the dirty fighting"; a trait that continued when they reached the Dutch town of Philippine in the Zeeland area of the Scheldt. It was here, according to his fomer Troop Commader where Moe “outdid himself.”

The recent inclement weather had made the terrain most inhospitable, particularly for tanks. Everywhere, muddy-green water inundated the roads and left the Dutch polder land a veritable quagmire, which forced tank crews to navigate the vast morass by following treelines or plodding along the raised dikes. With movement restricted to these narrow and extremely treacherous routes, Canadian tanks advanced at great peril, fully exposed to German landmines, anti-tank, and panzer gunners at long distance, tank hunting teams at close quarters, and deep, flooded ditches that straddled each road.

On September 20, Moe’s troop received orders to escort the Crusader tanks of the Guards reconnaissance unit (commanded by Lt. R.B. Verner) and B company of the Algonquin Regiment in their capture of the train station on the outskirts of Philippine, just over the Dutch-Belgian border. A quick look at the intelligence overprint that laid out suspected enemy locations, showed a sizeable German “hedgehog” position centred around a small clump of houses, slit trenches and hedges. This position would require attention before Moe’s tiny battlegroup could reach the town.

The advance kicked off late in the afternoon with Verner’s Crusader tanks in the vanguard followed by the infantry with Moe’s four Shermans bringing up the rear. The advance encountered few problems until the column slammed headlong into the “hedgehog” near last light. At that point, machine-guns concealed in the distance open up, forcing the infantry to dismount in the soaked fields on each side of the column. Instantly, accurate fire from a machine-gun concealed in one of the houses less than two hundred yards away opens up and pins the infantry down. Verner, hoping to push on with his tanks at the head of the column, discovers that the going is much more challenging than first imagined, forcing him to halt in an exposed and precarious position leaving, as he put it, his “hands tied.”

Guardsman RW Ferguson of The Canadian Grenadier Guards watches two French children examining his Centaur MkII anti-aircraft vehicle. Elbeuf, France

Clearly understanding the potentially fatal nature of the unfolding scenario, Moe ordered his Shermans up to a position where they could bring down direct fire on the Germans. The treacherous terrain and vehicle congestion along the only route forward quashed that plan instantly. As he had done earlier in Normandy, Moe yet again seized the moment and ordered his men to dismount and fight it out on foot. As Verner reported, Moe “jumped off his tank” armed only with his Sten gun, followed by two other crew members. The remainder, still in the tank, provided covering fire with tank’s machine-guns.

For 150 yards, the tiny band crawled through the mire, along the ditches and hedges towards the enemy, all the while subjected to waves of German fire. Closing on their target, they worked their way to the first house and with a “great shout,” Moe jump up, kicked in the door, and sprayed the interior with his Sten, killing three Germans and forcing the rest to surrender. From there, the trio continued on, clearing two more buildings and pair of elaborate trench systems before Moe decided to charge two German machine-gun positions alone. After killing or capturing their crews and turning his prisoners over to the Algonquins, he climbed back aboard his tank and resumed the advance.

No sooner had Mo reounted than all Hell broke loose. In the previous melee a German tank destroyer, sporting a deadly 88mm gun, had snuck into position and proceeded to pick off Verner’s Crusaders one by one. In a flash, Verner found himself in the watery ditch that straddled the road across the way from his friend, a fellow troop leader Lt. T.W. Birss, writhing in pain and in need of immediate medical attention. On its last shot, the panzer found “Geraldine,” forcing Hurwitz and his crew to escape before the tank “brewed up.”

Now, armed only with a pistol and suffering his second set of burns in just six weeks, Moe set out on foot yet again to settle the score. Commandeering a surviving Sherman and directing its fire, he drove the German armoured fighting vehicle undercover but failed to land the knockout blow. Dissatisfied, the determined Guards sergeant took to the wireless and called in artillery support to finish off the beast.

In the meantime, the Germans had grown more aggressive with their tank hunting teams, and when two Canadian infantry Bren Gun carriers behind Hurwitz went up in flames, the victims of German bazookas, it became clear the enemy planned to close in for the kill. Without hesitation, Moe jumped back into the ditch and proceeded to crawl the 50-yard stretch to the wounded Lt. Birss, dragging him back to safety while under German fire. Upon hearing that one of the young lieutenant’s crew remained trapped in his smouldering tank, Moe returned yet again down the ditch, braving enemy fire to drag the man out and back to safety before the Crusader exploded.

Once again, Moe’s unparalleled courage and bravery earned yet another recommendation for a gallantry award. At face value, many suspected his actions at Philippine would garner the Victoria Cross - the highest award for gallantry available in the Canadian army. In the end, he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his “determined and gallant action.” Moe likely knew about his write-up for another commendation, but would never learn of its sanction, for a month later, the legendary luck of the Guards’ sergeant ran out.

Sgt Moe Hurwitz's medals.

By late October, the Battle for the Scheldt had entered its closing phase, with the 4th Canadian Armoured Division pushing towards Bergen Op Zoom, attempting to open the road from Antwerp to Bergen and cut off the remaining retreat route for the enemy. Blocking this drive was the tiny Dutch hamlet of Wouwesche Plantage held by elements of the elite and fanatical German 6th Parachute Regiment supported by a collection of assault guns, tank destroyers and anti-tank guns. Stubborn resistance over the previous few days had led Canadian intelligence to admit “that there is little doubt the enemy’s best troops are in this sector.”

The task of capturing the town was given to the CGG, working in conjunction with two infantry companies of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada. Unlike earlier attempts, this attack would go in before first light on October 24, 1944. Once again, the attack would be put in “at all costs’.

As Major George Hale, Moe’s Squadron Commander, recalled, “it was a dark night” with only a “minimum amount of visibility made possible by the fires in the area” when his force moved out. The eeriness of the late October night accentuated by 72 hours of steady, dreary rain that had fallen, made the already treacherous conditions worse, stirring up the ghosts of Passchendaele in 1917 where the Guards toiled in mud and blood of combat in Belgium during the First World War. Bottomless pools of water and mud, enemy artillery fire of an intensity not yet seen, hastily laid land mines and booby traps, impromptu roadblocks, tank-hunting teams laying in wait, and snipers with a penchant for exposed tank commanders, all painted the backdrop for the approach to Wouwesche Plantage.

The plan was to execute a fast run up the road leading to the town, taking the Germans by surprise. The ruse worked for the most part as many startled Germans were rounded up and taken prisoner during the advance. At 0515 hours, not long after the attack began, Moe, moving in the lead tank, reported back to Hale that he had reached his objective in the town “but did not know what had happened to the tanks supposedly following”. He reported small arms and bazooka fire as “quite intense.” Unable to see from his position nearly half a mile behind, Hale was shocked at the speed of Moe’s progress, for he had received conflicting reports that the movement of the rest of the battlegroup had stopped for some unknown reason about 300 yards short of the objective.

Further enquiries revealed that the second tank, commanded by Moe’s friend Sgt R.W. McAuley, had fallen victim to a German bazooka. It now sat abandoned, blocking the road with the crew falling into German hands. With the ground on each side too soft for vehicles, the column ground to a halt with Moe’s tank cut off on the other side. Realizing he was a sitting duck, Moe ordered his tank to resume the advance top speed towards the objective, radioing back that “I seem to be in a bit of a spot. I am going forward. Follow me when you can.”

Every wireless set in the regiment then kept a keen eye out for any message from Moe. At 0520 hours, just five minutes after sending his message that he reached the objective, Hale tried to raise Moe on the wireless to issue new instructions but noted with despair, “a reply was not received.”

In the interim, several attempts by the Guards to clear MacAuley’s tank failed, drawing only German fire that also disrupted an attempt by the infantry to push forward. Wwhen the sun came up ifteen minutes later, the entire force pulled back to consolidate the ground gained with no word from Moe or the other four men in the crew.

The next day, the Guards overran the town but could not locate Moe’s tank, nor did they find signs of casualties in the immediate vicinity. Hale immediately began to question German prisoners and Dutch civilians who now packed the streets to welcome their liberators. The prisoners revealed that they had indeed captured a tank but reported it had been either driven or towed away. They also revealed that roughly nine Canadians had fallen into German hands, but that remained unconfirmed. A short time later, a German wireless broadcast mentioned three of Moe’s crew by name – Guardsman J. McLeod, R.C. Sanderson his gunner Ernest Therrien – as having fallen into their hands but did not mention Moe’s name or that of Corporal Copping. The evidence was both scanty and circumstantial. As Moe’s friend, the Guards Quarter-Master Sergegent Art McCormack confided in his diary that night: “Sgt. Moe Hurwitz, his crew and tank reported missing today. I hope to goodness they find him because he would be a serious loss to this unit, not to mention how awful I feel.”

Listed officially as “Missing” and without official word from the Germans for months, rumours swirled concerning his ultimate fate and treatment in the hands of the Nazis. Fueled in large part by a suspect story of the discovery of Moe’s paybook ten miles from Wouwesche Plantage, many recalled Moe’s steadfast refusal to have “Jewish” omitted from all forms of identification underscored by his vow to never be taken prisoner.

“...in his delirium, he was shouting commands over his tank radio to the tank driver and gunner directing fire...”

However, it wasn’t until March 19, 1945 when confirmation came through German channels that Moe had “died of wounds” while in their hands on October 26, two days after he disappeared. Only when the war ended in the spring of 1945, and those captured on that night came home, was the mystery partly solved.

Guardsman Herb Poole, one of Sgt. McAuley’s crew, wrote to Hale that Moe “died at the hospital in Holland” after being evacuated across the Moerdijk Bridge over the Maas River, through Steenbergen where they discovered his paybook, to a German hospital south of Rotterdam near Dordrecht. As Poole related, Moe had been “shot through the right lung” after bailing out of his tank following “two or three hits” from a German bazooka. “He was delirious and thought he was talking to you on the wireless,” Poole told Hale. “ I was with him in the hospital because I got it in the shoulder and leg when they hit our tank from behind with a bazooka.”

Further corroboration came years later from Moe’s gunner Therrien and also from an infantryman from the Lincoln and Welland Regiment captured on the same day, Private Alfred “Fred” LeReverend. Therrien, who had been wounded by shrapnel in both legs, confirmed that his sergeant had indeed taken a bullet in the right lung while LeReverend, who only met Moe during the two-day journey to the German hospital, had this impression seared upon his memory :

“That first night, I sat up with a delirious, badly wounded tank commander…from the Grenadier Guards. He’d taken a bullet through his lung, and throughout the night, he kept reliving, over and over again, his last tank battle. In his delirium, he was shouting commands over his tank radio to the tank driver and gunner directing fire; and then he would berate himself for being unable to carry on fighting. I tried to convince him that his Squadron Commander had ordered him to pull out and rest. Obviously a very dedicated and brave soldier, for draped over the back of the chair beside the bed, was his tunic with sergeant's stripes, and above the left breast pocket the coveted and very rare Military Medal for bravery. Glancing through his paybook for his particulars, I discovered that he was from Montreal, and his religion was listed as Jewish. Orange froth had begun to collect around the right corner of his lips, and….I went to get help from the night orderly. Quietly, the Orderly indicated to me that my friend would soon die and then graciously stated that it was the first time he’d ever seen or ever heard of ‘Judische’ in Battle.”

“That first night, I sat up with a delirious, badly wounded tank commander…from the Grenadier Guards. He’d taken a bullet through his lung, and throughout the night, he kept reliving, over and over again, his last tank battle. In his delirium, he was shouting commands over his tank radio to the tank driver and gunner directing fire; and then he would berate himself for being unable to carry on fighting. I tried to convince him that his Squadron Commander had ordered him to pull out and rest. Obviously a very dedicated and brave soldier, for draped over the back of the chair beside the bed, was his tunic with sergeant's stripes, and above the left breast pocket the coveted and very rare Military Medal for bravery. Glancing through his paybook for his particulars, I discovered that he was from Montreal, and his religion was listed as Jewish. Orange froth had begun to collect around the right corner of his lips, and….I went to get help from the night orderly. Quietly, the Orderly indicated to me that my friend would soon die and then graciously stated that it was the first time he’d ever seen or ever heard of ‘Judische’ in Battle.”

When Moe was still considered “missing” in January 1945, the Canadian army gathered up his personal effects to send them to his family. Among the inventory list were 17 handkerchiefs. It isn’t known why there were so many.

Perhaps they came inside the monthly care parcels sent by Canada’s Jewish community to the men and women of Jewish faith who were serving overseas. Nearly 17,000 Canadian Jews served in the Second World War, and Moe is one of nearly 450 who didn’t come home.

Perhaps he had bought them as souvenirs, intending to send them home as gifts.

After Moe’s brother Harry Hurwitz was liberated from the German POW prison camp in the spring of 1945, he made his way to England. That’s where he ran into some men who had known Moe. He learned then that his brother was dead.

Harry was devastated, but not surprised. Moe had told his brothers that he knew he would not be returning from the war.

“‘Don’t worry, Harry, I won’t be back. You look after yourself’,” Harry recalled.

After the war, forensic investigators were sent out to scour the European countryside looking for the graves of those Allied soldiers and airmen who had been killed and buried by the Germans or by local villagers. The plan was to locate the bodies, then exhume them and reinter the fallen in a series of carefully maintained, centralized Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries.

The Hurwitz family was desperate to find out exactly what had happened to Moe, and where he was buried. His mother, Bella, wrote to the Red Cross in Ottawa in July 1945, appealing for details.

It would be October before investigators could inform the family that Moe’s grave had been discovered in a communal cemetery near where he had been treated in the German hospital in Dordrecht, Holland. The grave was located in Field N, Row A1, Grave 10. The army also noted Moe was Jewish, and that he had been buried with “religious rites”. They promised to send photographs of the grave and the temporary wooden Star of David which they said marked the spot.

While the family waited for news, Canada’s Jewish community published a book in 1947 devoted to the nearly 200 Jewish men and women who had won medals, including Moe. The book devoted seven pages to Moe; the most space given to anyone, even though Moe was not an officer, just a sergeant.

Unlike the heroes who survived the war, Hurwitz would never experience the celebrity of being summoned to Buckingham Palace to receive his gallantry awards. Moe’s Father Chaim travelled to Ottawa to receive them from the Governor General.

The archives of the Canadian Jewish Congress in Montreal also contain the proofs for a comic book about Moe, entitled “Some Never Die”, that was supposed to be printed and distributed for free to local children after the war. It is not certain that the comic was ever published.

Moe’s remains were eventually transferred to a permanent resting place in the Bergen-Op-Zoom Canadian Military Cemetery in Holland. Officials knew Moe was Jewish, as it said as much on his paperwork: Moe had written the word “Hebrew” in six different places in one of his personal army service books, which was recovered.

Somehow, a wooden Cross was erected on this new grave, rather than a Star of David. With the best intentions, the military sent two photos of the grave marker to the Hurwitzes, unaware of the shock and distress these photos would cause.

It would take a flurry of letters back and forth until the family was informed the mistake had been corrected. The Canadian military admitted it was “embarrassed” due to the soldier’s “excellent military record” which “has been publicized considerably in this country”. Canadian officials asked the war graves authorities to have the work done quickly, as a special case, and asked that new photos be sent forthwith to the family.

The new tombstone at Bergen-op-Zoom Canadian War Cemetery has the Star of David, as well as information in Hebrew about Moe’s next of kin, and the Jewish calendar date of his death. The loss of Moe, who was only twenty-five, was never far from his brother Harry’s thoughts, or Harry’s children.

Decades ago, Harry’s daughter Debbie Hurwitz Cooper paid her own tribute to her famous uncle by naming her son Michael after him.

“This man deserved to be honoured as long as people care to remember him. He was totally, totally selfless and fearless and he just wanted to help his fellow Jews. He wanted to see justice. He wanted to see people treated well,” she said.

Despite the passage of more than seventy-five years since Moe’s death, his legacy continues to resonate as other people outside his immediate family discover his story.

Library and Archives Canada released his original military records to the public for Remembrance Day 2015, when a popular international genealogy company, Ancestry.ca, picked Moe as one of three Canadian war heroes to showcase.

He even appears as a character in the fiction books and stories of American crime writer Shelly Reuben. The Brooklyn author and columnist is Moe’s niece. She says the whole family considered Moe larger than life and was inspired by his example.

“When you have someone like that in your family, you can never not live up to your best,” Reuben said.

The legacy and the challenge of Moe Hurwitz’s life were also passed on to new generations of Canadian military personnel through Hurwitz’s regiment, the Grenadier Guards. The “Hurwitz Cup was awarded each August to the army cadet with the highest score in marksmanship at the Connaught Ranges, near Ottawa.

The Guards Museum in Montreal also displays Moe’s bravery medals, and the Silver Cross that his mother Bella received from the government, after his death. A ten-page commemorative booklet pays homage to their “most purposeful and persistent soldier”.

Harry Hurwitz would undoubtedly have liked to pay one last visit to Holland to see his brother’s grave, but just before this story was published, the Montreal navy veteran and former POW died Oct. 18, 2020, at the age of 99.

DAVID O’KEEFE is an award-winning historian, documentarian and professor at Marianopolis College in Westmount, Quebec. He served with the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada in the Canadian Forces in Montreal and worked as a signals intelligence research historian for the Directorate of History and Heritage. He created and collaborated on more than fifteen documentaries for the History channel and National Geographic and has appeared on CBC, CTV, Global Television and the UKTV Network in Great Britain. He wrote and co-produced the groundbreaking documentary Dieppe Uncovered, which made headlines around the world, as well as the documentary Black Watch Snipers. He is also the writer, co-creator and host of the History channel’s program War Junk. In addition, he is the bestselling author of One Day in August: The Untold Story behind Canada’s Tragedy at Dieppe, a finalist for the John W. Dafoe Book Prize, the CAA Lela Common Award for Canadian History and the RBC Taylor Prize. David O’Keefe lives in Rigaud, Quebec, with his wife and children.