Why were Canadian troops sent to Hong Kong?

By late 1941, relations between Japan and Britain had deteriorated. There was fear among British government and military officials that Japan would declare war on them and attack their colonial possessions in East Asia. Many in the British military believed that sending reinforcements to their colonial garrisons would deter Japan from starting a war in the Pacific. Most government officials were against such a course of action but later changed their minds as the situation changed in late 1941.

It was at this point the process that sent Canadian troops to Hong Kong began. Canadians came to be considered for the defence of Hong Kong because of Brigadier Arthur Edward Grasett, the former commander in Hong Kong. Grasett was returning to Britain through Canada, a standard practice for previous British commanders in East Asia.

During his journey he met with the Canadian Chief of General Staff Major-General Harry Crerar and Canadian Minister of Defence J.L. Ralston, possibly several times. Crerar later denied that the possibility of Canadian troops being sent as reinforcements to Hong Kong was discussed. The nature of these discussions is not fully known but given what followed it is very likely that the possibility of Canadians reinforcing Hong Kong was discussed over the course of the meetings.

Upon reaching Britain in early September 1941, Grasett met with the British Chiefs of Staff and suggested that Canadian troops could reinforce Hong Kong. The Chiefs of Staff accepted the suggestion and on the 19th of September, the British Dominions Office cabled Ottawa, asking if Canada could provide troops to reinforce Hong Kong. Shortly after receiving the request, and with little debate, the Canadian War Cabinet Committee accepted.

Even before the request was accepted, a search for which units to send to Hong Kong had begun. Crerar, after consulting numerous officials in the Department of Defence, selected the Winnipeg Grenadiers and Royal Rifles of Canada to form the core of the Canadian force sent to Hong Kong. It is often believed these units were labelled as unfit for service. This was not entirely true as the policy was that units that returned from overseas assignments had to undergo training before being sent overseas again. Neither of these units had this refresher training when selected for “C” Force, the name given to the Canadian reinforcement.

The First Canadian Contingent lands at Hong Kong 16 November 1941.

Japanese troops enter Hong Kong led by Lieutenant General Takashi Sakai and Vice Admiral Miimi Massichi, 26 December 1941.

The Battle of Hong Kong

The Canadians arrived in Hong Kong in late November 1941, giving them little chance to acclimatize to their new post. The battle began on the 8th of December 1941 with the Japanese attack on the mainland portion of the colony, known as the New Territories. The defensive line, known as the Gin Drinker’s Line, was expected to stall a Japanese attack for an extended period of time but fell within a day. The collapse of the Gin Drinker’s Line forced a retreat of garrison troops to Hong Kong Island, which was completed on the 11th.

Japanese troops landed on Hong Kong Island and quickly pushed into the island’s interior leading to fighting at the Wong Nei Chong Gap, the location of some of the most intense fighting experienced by Canadians during the Battle of Hong Kong. The resulting fighting killed Brigadier J.K. Lawson, commander of “C” Force, on the 19th of December. “D” Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers was also cut off due from this attack but stubbornly defended their position for several days before surrendering.

The fighting on Hong Kong Island was defined by counterattacks. The island is dominated by several hills which are critical to control movement among its roads. Many of these hills changed hands frequently as the garrison’s troops could not allow these positions to remain in enemy hands. Thus Canadian, British, Indian, and Hong Kong troops needed to counterattack anytime the Japanese established themselves on one. As the battle raged on, the garrison counterattacks became more and more futile. Many times, Canadian troops fought to gain positions atop a hill, only to retreat when they were exhausted from the effort. They would take casualties that could not be replaced. The Japanese had a numerical advantage, so the attritional nature of the fighting was to their benefit.

Such one counterattack that was indicative of the Canadian experience at Hong Kong was “D” Company of the Royal Rifles Christmas Day attack on Stanley Village. Initially the Canadians pushed the Japanese out of their positions in the village but Japanese equipment and numerical advantage forced the Canadians back again with many casualties. This last-ditch undermanned and underequipped counterattack symbolizes the Canadian struggle at Hong Kong.

After very difficult fighting, Hong Kong’s garrison surrendered on Christmas Day 1941. The defenders had put up a stout defence but Japanese material, numerical, and tactical advantages proved to be too much. A total of 290 Canadians died in the battle. The entire Hong Kong garrison suffered 4,413 casualties, which includes 2,113 killed in action. The Japanese lost 675 killed and 2,079 wounded.

Battle of Hong Kong Story Map

Infantrymen of "C" Company, Royal Rifles of Canada, disembarking from H.M.C.S. PRINCE ROBERT, Hong Kong, 16 November 1941

Personnel of the Winnipeg Grenadiers and Corps Troops entraining en route to Hong Kong

Infantrymen of "C" Company, Royal Rifles of Canada, aboard H.M.C.S. PRINCE ROBERT en route to Hong Kong, 15 November 1941

Infantrymen of "C" Company, Royal Rifles of Canada, and their mascot en route to Hong Kong. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, ca. 27 October 1941

Company Sergeant-Major J.R. Osborn of "A" Company, The Winnipeg Grenadiers, Jamaica, ca. 1940-1941. Killed in action at Hong Kong on 19 December 1941, CSM Osborn was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross

Hong-Kong defences, site at Wong Nai Chong Gap where West Brigade Headquarters, and Winnipeg Grenadiers were over-run by Japanese forces, 19 Dec. 1941

After the Battle

The cessation of hostilities did not stop the Canadians from dying. The Canadians were subjected to nearly four years of brutal conditions in Japanese prisoner of war camps. Conditions in the camps quickly deteriorated due to overpopulation and Japanese negligence. Many died from diphtheria, dysentery, typhoid fever, and malnutrition.

The Japanese also took Canadian lives including the August 1942 execution of Sergeant John Payne, Corporal George Berzinski, Private J.H. Adam, and Private P.J. Ellis. They were recaptured following an escape from the Sham Shi Po camp and killed. Some of the worst punishment doled out to Canadians was by Kanao Inouye, a Canadian who was serving in the Japanese Imperial Army. He was born in Kamloops, British Columbia and thus nicknamed the “Kamloops Kid” by the Canadians. He was executed for treason by the Canadian government after the war.

Starting in 1943, Canadians were sent in drafts to Japan to work as slave labourers in mines, factories, ports, and rail yards. More lives were lost to dangerous work conditions and the poor treatment received from the Japanese. In a deliberate act of sabotage, some Canadians shut down the Yokohama shipyard by burning all the blueprints of the ships. The prisoners of war began to be liberated in September 1945 after the Japanese surrender to the Allied powers. As a result of the poor conditions and treatment a further 280 Canadians died.

Many Hong Kong veterans suffered from numerous ailments including alcoholism, psychological issues, and general poor health upon their return home and for years afterward. Many were denied proper care by the Canadian government, an error that was only rectified after most of the Hong Kong veterans had passed away.

Hong Kong Prisoners of War

Force C Personnel Database

Additional Resources

Project ‘44 is very thankful to have received the support from both the Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association (HKVCA), and Dr Kwong from the Hong Kong Baptist University whose team created the “Battle of Hong Kong 1941: a Spatial History Project”. Both organizations provided invaluable data to help us build our web maps, generate war diaries, and build a personnel record database for the public to explore.

Please consider checking out both of these organizations to further your understanding of the Battle of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association

Hong Kong Baptist University

The role of the Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association to educate all Canadians on the role of Canada's soldiers in the Battle of Hong Kong and on the effects of the internment of the battle’s survivors on both the soldiers and their families. We also assist in the support and welfare of Hong Kong veterans and their widows.

The spatial history project “Hong Kong 1941” uses geographic information systems (GIS) to build a web map about the Battle of Hong Kong and a database of British military installations in Hong Kong during the Second World War. It offers an easy-to-use historical database for educators, tourists, and conservation professionals.

Support the project:

How can you support the project:

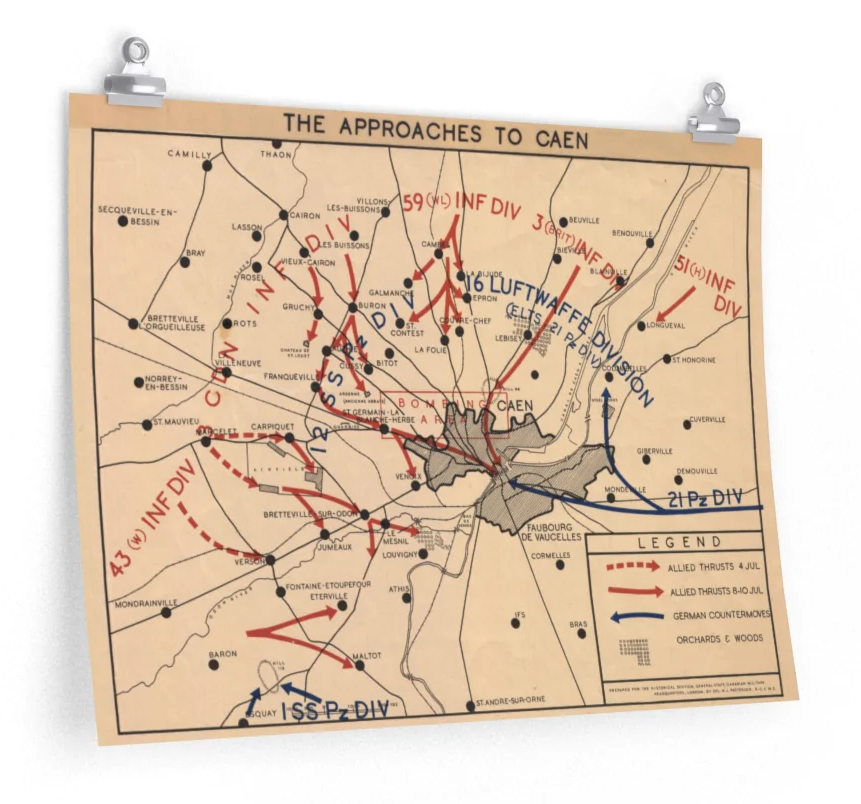

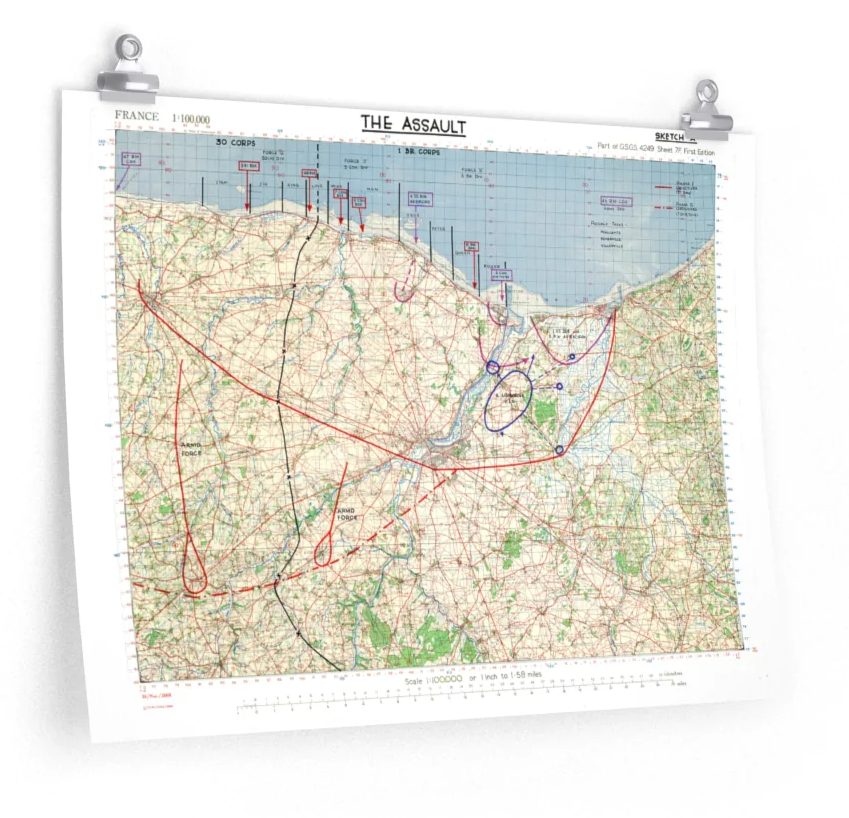

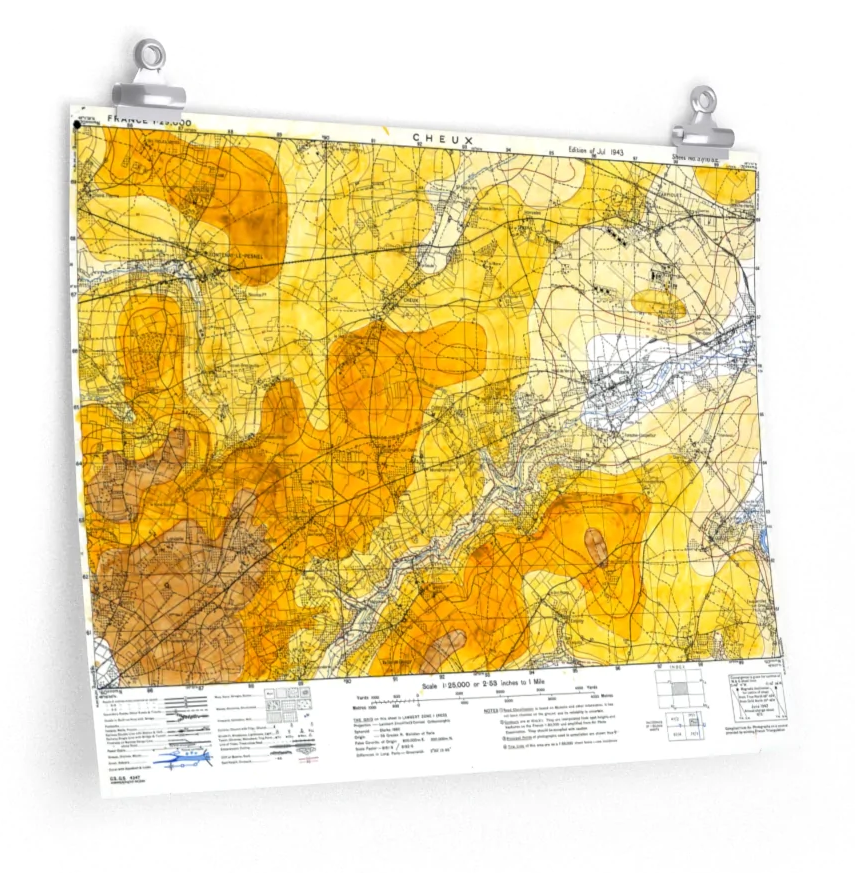

Buy a map today!

We sell dozens of authentic maps covering DDay, Monte Cassino, Dieppe, Market Garden and more. These are high resolution scans of original maps that you can only find in the archives.

Each map is printed on high quality paper ready for mounting in a frame for your office or living room.

The best part of buying a map? 100% of proceeds are directed back to the project allowing us to continue to map out the Second World War.

Other ways to support the project:

Donate

You can help us tell the story of Canadian soldiers by donating today!

Our team is dedicated to keeping the story of Canada in the Second World War at the forefront using interactive technology that makes history open and accessible.

With your donation you help us to keep mapping and digitizing war diaries so we can continue to tell the story of those who served and those who fell.

Join Patreon

Do you want to become part of the team? Consider joining Patreon!

As a member of Patreon you can influence our project, what we are working on, and can even direct message our team. As a Patreon you can even get discounts to our entire store!

With your membership you can show your commitment to the project by helping us every month. And the best part is, every Patreon dollar goes directly to the web map!